How do you bring hope to the harsh, suffering-filled world of prisoners? Zoltán Stift, who has been serving as a prison chaplain and coordinator of prison chaplains for 10 years, knows this dark world, but always finds hope in the conviction that life has sustaining meaning for man, since man is important to God. Because of the coronavirus pandemic, our conversation took place in the Pauline Library of the Central Priest Seminary building and not in the prison building. Interview by Éva Trauttwein.

This article was originally published on our sister-site, Ungarn Heute.

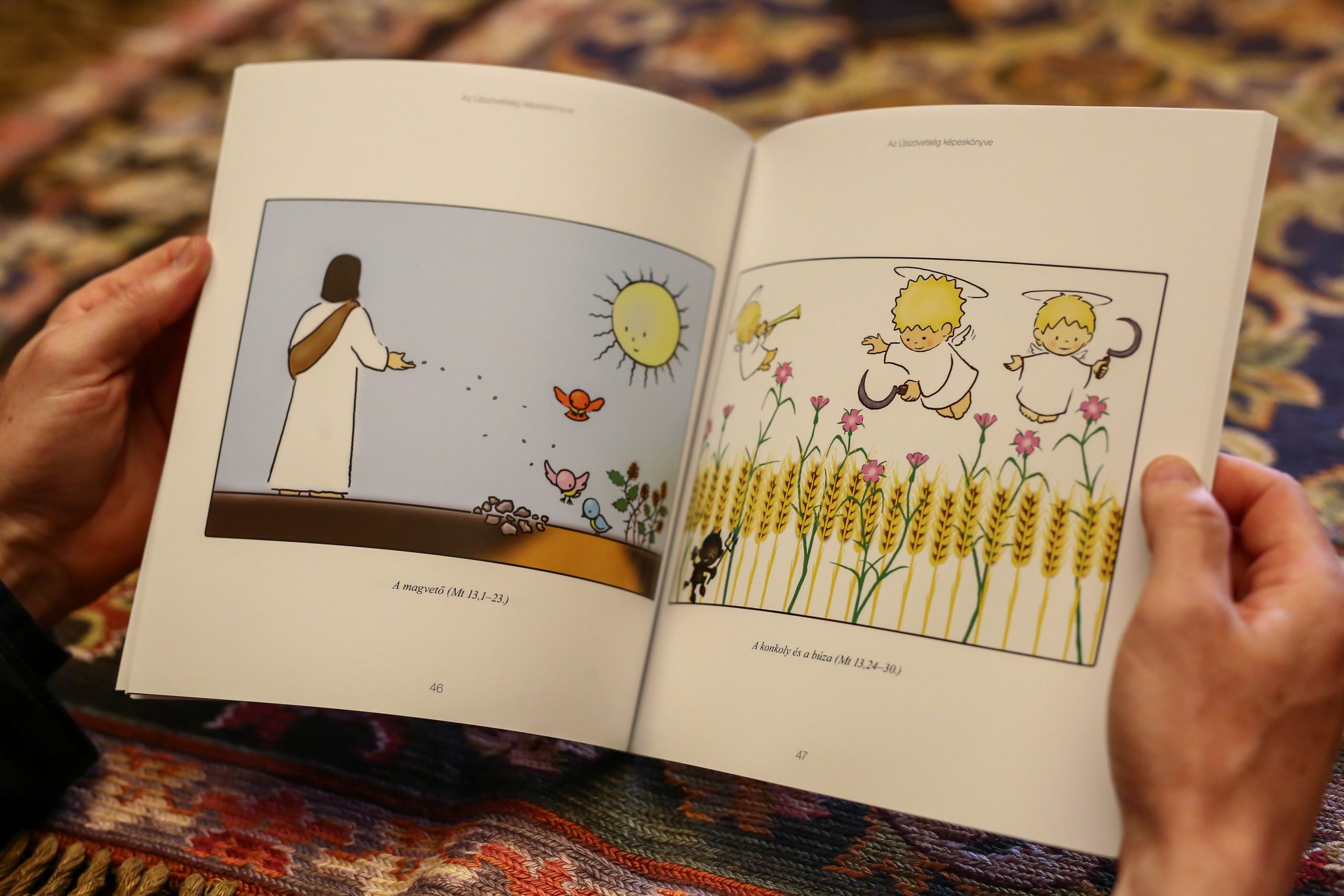

Zoltán Stift is known as Father Angelico for his biblical drawings. How did you get into prison chaplaincy?

Drawing for me is a way of evangelization, a kind of vocation. I am often invited to public meetings, my drawings are often exhibited.

Photo by Attila Lambert

I did not want to lose that, but from my diocese – Szombathely – which is located in western Hungary, nationwide contact would be limited. I was offered the position in Budapest as a prison chaplain.

Neither as a child nor as a priest does one dream of serving among prisoners. But when life brings that, one recognizes in it one’s own task. The priest, even God, is sought above all by suffering people. So I did not feel a great difference between serving in the parish or in prison.

What attracted you to this work?

The presence of the Church, perceived through the person of an ordained priest, is of existential importance in prison. You can’t hide behind formulas of faith, you have to face existential questions. The goal is not to proselytize, but to be there for the people and to give them a hint as a person of trust. The essential thing is to be there as a priest. I am most challenged in prison, so this activity has largely strengthened me in my vocation.

Photo by Attila Lambert

What do you consider to be your task?

Pope Francis says the shepherd is in the midst of the sheep, shepherding and encouraging the flock. This is our task among the imprisoned. To accompany, to support, to give meaning to life, to listen. Prison chaplaincy is not justice, but the care of suffering. I always say to myself: the judgment in me must die. I must bring life and mercy to the people.

The people living there have been rejected by society. They often have nothing and no one that could give them purpose and meaning, they are left alone with their own guilt, worries, and fears. They have to cope in the tough world of prison.

In order to survive, they need daily encouragement. Even people who had no connection to the church find support in religion here; the church has something to offer them from its great treasure of faith.

Soon we will celebrate Easter. What can bring hope to the prisoners?

At the center of my pastoral ministry is the celebration of Mass. God comes into our midst in this forsaken world. Behind the bars, in the offering of bread and wine, Christ who gives himself for us is present. Christ suffered and died on the cross. Experienced abandonment. Would that be a failure? Perhaps, but that sacrifice brought us redemption. That gives hope, that gives meaning. Easter speaks about how human existence is more because man is loved by God.

During the Easter season, conversations with prisoners and also with staff are increasingly important. In every festive season fears about the family and the future come up more and more. Feelings of guilt and powerlessness paralyze people. Locked in, they can do nothing for their loved ones. Conversations bring people to other thoughts. In the church services and group meetings, we experience community.

A great delight is that the inmates, men between 20 and 50 years old, love to sing. Singing together gives them joy.

How do you experience it: do people receive what religion offers?

We would be on the wrong track if we said to the detainees, that faith in God fills you with pure joy, and lifts you up.

Yes, life gets better through faith, but not easier. People need encouragement every day.

In the conversations I experience, when I meet them with goodwill, completely without reproach, they open up and tell me dark stories from their lives, which they would not confide in anyone.

Photo by Attila Lambert

What is your relationship like with the prisoners?

It is similar to the relationship with believers in the church. I am a priest for them. We get along well, laugh and cry together. In the conversations, I ask questions, confront when necessary, and do not withhold my view, but I do not condemn anyone. Closeness and distance are important at the same time. I talk to everyone who asks me to.

The prisoners are good judges of character. The priest is an open book for them. If we are honest among them, our very existence has a positive effect.

Is the moral, life-guiding teaching of the Church compatible with prison life?

If we understand them correctly, yes. A Christian is not an emotional, prissy aesthete, but a person who relies on divine care, who trusts God, and who acts with heart and mind. Love obliges, leaving no possibility for the other to commit sacrilege. A great temptation is to see life as meaningless. For whom should I pull myself together? Many have no one and nothing as a goal. If you can’t get a grip, jail sucks you in. I have the task of always finding hope myself and offering the source of my hope to the community.

Written by Éva Trauttwein. Featured image and photos by Attila Lambert.