This year, the event will be based around the slogan "We are in the Trend" and will be held in Veszprém, the European Capital of Culture.Continue reading

Óbuda’s past is mostly associated with its ancient Roman heritage, but the city of the former queens was also an important settlement in the Middle-Ages. On the occasion of Archaeology Day, we followed the traces of the medieval city on the Óbuda Museum’s city walk, as reported by Kultura.hu.

In the Middle Ages, Óbuda (Buda until the 13th century) was first a princely, then royal, and later a queenly center. At the time of the foundation of the St. Peter’s Church in the 11th century, it was a chaplaincy center, and a substantial Romanesque provostry church, built on the site of today’s Szentlélek tér – Fő tér (Main Square).

Photo by Margit Móricz from: Facebook

The Chapter, both an ecclesiastical and a legal body, was a national authenticating authority, i.e., it had the right to issue a document certified by its seal on any legal transaction.

The Church of St. Peter was built on the demolished foundations of the former Roman military town, using its stones. The basilica, with three naves, would have been seventy meters long and thirty to thirty-five meters wide. It was badly damaged during the Mongol invasion to the extent that it could no longer be rebuilt.

Remains of a Gothic church were discovered during a sewerage project in Fő tér in 1935. This was the Church of the Virgin Mary, built on the orders of King Louis the Great’s mother, Elisabeth Piast.

A model reconstruction of the Church of Saint Mary in the XIVth Century; Photo: Facebook/Óbudai Múzeum

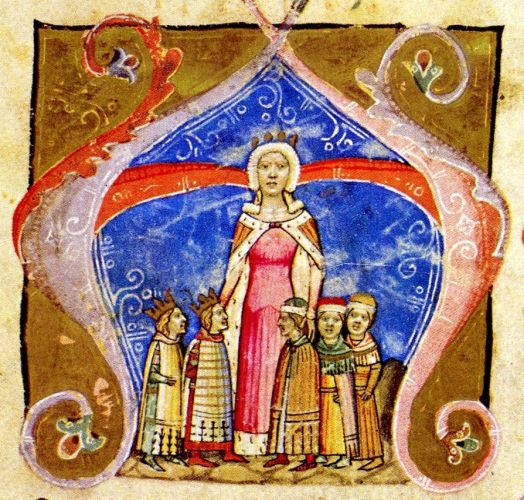

At the age of fifteen, Elizabeth Piast became the wife of the 32-year-old Charles Robert, who had no descendants by previous marriages. Elizabeth had five sons, including the future king: Louis the Great. The Polish-born queen retained her strong influence even after her husband’s death, acting as a co-ruler with her son and having a say in political matters. At the age of twenty-five, she lost four fingers on her right hand in an assassination attempt by Zách Felicián, but this injury did not hinder her long and active life.

Elizabeth Piast; Photo: Wikipedia

The Church of St. Mary was built next to St. Peter’s in the 14th century, but it was smaller than its predecessor. The German-born architect Corradus Theutonicus designed his Gothic hall church in the tradition of southern German church architecture. Its destruction began with the Turkish invasion of Óbuda in 1529, when its stones were carried away to build mosques and baths, and after the Ottoman period, it was used for the Zichy castle and for building works in the surrounding area.

The first University of Buda, founded in 1395 by Sigismund of Luxemburg, is also worth a visit when walking along the Main Square in Óbuda. The school, which had four faculties, was not long-lived, with no records of its operation between 1403 and 1410, and after 1419, no further record at all. A relief on the high school wall in the Main Square commemorates the school.

Photo: Facebook/Óbudai Múzeum

In the Middle Ages, the mendicant orders built their houses on the outskirts of the town. The remains of a Franciscan monastery were discovered in 1973, during the construction of a housing estate on the Main Square (Fő tér), which made it possible to identify the former extent of the medieval town. Interestingly, it was also built on Roman foundations, and the underfloor heating of the former Roman building was incorporated and used in the monastery’s dining room.

The founder of the Franciscan Order, St. Francis, came from Assisi, just like St. Clare, the founder of the Clarissan Order and a follower of St. Francis. Alongside the Franciscan order, the Clare nuns also settled in Óbuda, building a monastery and church with the strong financial support of the deeply religious Piast. Elizabeth was buried here, and her remains were taken to Bratislava (today Capital of Slovakia, Pozsony in Hungarian) to escape the Turkish invasion, but afterwards disappeared.

Her house altar, once set up in the Clarissa monastery, is now on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Facebook/Óbudai Múzeum

Traces of the former church can also be found beneath our feet: it stood on the site of the present Baroque church of Saints Peter and Paul, its layout marked by a pattern of pink stones contrasting with the grey cube stone.

Photo: Facebook/Szent Péter és Pál-főplébánia-templom

After the sacred buildings, we followed the secular architecture of the former royal castle. It was begun by Andrew II in 1210, but was probably badly damaged during the Mongol invasion and only restored by Elizabeth Piast between 1343, and 1380. Louis the Great gave the castle to her as a gift, so that its revenues enriched the queen. The square castle, surrounded by double walls and moats, also used floor heating dating from the Roman period. The remains found and excavated in the cellar of the Reformed church in Óbuda bear witness to this. The castle also shared the fate of medieval Óbuda: it was not rebuilt after the Turkish invasion.

In the royal quarter, the market was located in the square in front of the current synagogue. The proximity of the Danube harbor made it a particularly suitable location, surrounded in the Middle Ages by a row of high-rise houses housing inns, meat shops, and craftsmen’s shops. It is here that Óbuda’s only medieval dwelling house, the house of Deák Ferenc, stands. The building, which now houses the Budapest Gallery, has only medieval walls but a modern interior.

Photo: Facebook/Óbudai Zsinagóga

Via Kultura.hu; Featured image: Facebook/Visit Hungary