Knowing which planets are passing close to Earth is crucial, as any one of them could pose a threat to humanity.Continue reading

An international team using a mathematical model developed by researchers at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics (BME) has solved the mystery of how cracks could form on the surface of planets. The new model could help to identify areas where water may have once existed, the HUN-REN Hungarian Research Network and BME revealed in a joint release.

Planets are often covered by thin, cracked shells. Researchers from the HUN-REN-BME Morphodynamics Research Group and the University of Pennsylvania have developed a model to describe the evolution of these crack networks over time. The results were published on Tuesday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The study is based on a mathematical model that can approximately reconstruct the entire evolution of the crack pattern based on a single photograph of it.

The model, the first of its kind ever applied to other planetary surface patterns, was developed by Hungarian researchers using a previous study they conducted with Péter Bálint, Director of the BME Institute of Mathematics.

The input to the model is one of the most basic features of the pattern in the photograph: the geometry of the nodes. Analytical and numerical calculations on the model have allowed researchers to identify three main types of crack patterns based on this feature:

Hungarian and US researchers say that analyzing the geometry of the cracks can help identify areas on the planet’s surface where water may have once existed or currently exists.

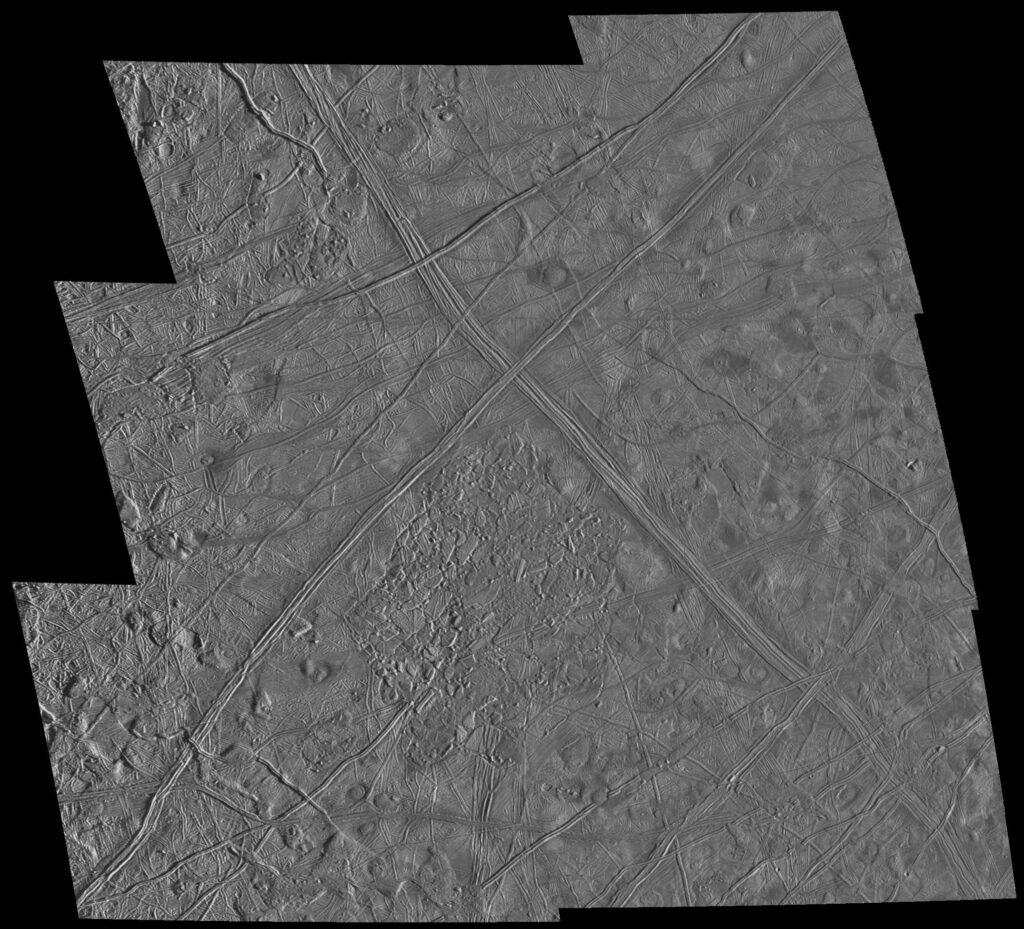

For instance, in the case of Mars, hexagonal crack networks suggest that regular water movement may have occurred in the past. On Europa, transverse cracks support the hypothesis that there may be a liquid ocean beneath the ice shelf that could provide a favorable environment for life.

Six-frame mosaic of Europa’s surface showing the prominent “X” near the center. Photo via NASA/Wikipedia.

The new model will allow image analysis methods to be used to systematically map the crack networks, allowing geologists to draw meaningful conclusions from the huge data set in a short time.

“Just as an artist’s photograph may contain a whole story, we can infer the past and future of a pattern from combinatorial averages measured on its current state. These patterns evolve in accordance with universal rules, and the model can be parameterized according to the material and the environment,” explained Gábor Domokos, professor at the Department of Morphology and Geometric Modelling at the BME Faculty of Architecture and head of the HUN-REN-BME Morphodynamics Research Group.

The results of the study provide a new tool for planetary science.

The analysis of crack patterns may in the future help us to study the surface of celestial bodies from which satellite images are available. It could help identify sites where water may have played a significant role in the formation of the surface morphology, and thus may have provided the conditions for life,”

the release quotes the leader of the Hungarian research team.

According to Krisztina Regős, another Hungarian author of the study, the next step could be the automation of methods, such as the development of artificial intelligence-based image analysis systems that would allow more accurate and efficient identification of crack networks in space images.

Via MTI, Featured image: Pixabay