The Roman Catholic priest, Bishop of Pécs, and first known Hungarian poet and humanist was born 589 years ago today.Continue reading

At the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, he sat in the highest offices and in prisons. Miklós Bethlen, Transylvanian writer and statesman, was a far-sighted, sober, public-spirited, and educated man, a supporter of peace and a pragmatic politician. He celebrated the anniversary of his birth at the beginning of the month.

After the Renaissance and before the Enlightenment, he was one of the best Hungarian prose writers. His autobiography is almost like an encyclopedia of the second half of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century.

Miklós Bethlen de Bethlen was born on September 1, 1642. His father, John Bethlen, once Chancellor General of Transylvania, was himself an educated man who, as an aristocrat, married a wealthy bourgeois girl, Barbara Váradi. Miklós Bethlen was often accused of having “merchant blood” flowing in his veins.

No doubt he inherited much of the practical sobriety of his Klausenburg merchant ancestors.

His origins probably also strengthened him in his virtue of not harboring any pride of station.

Photo via Facebook/ Gaus Péter

He was an excellent student: his teacher, role model, and mentor was János Apáczai Csere, the first Hungarian representative and advocate of Cartesianism (a from of rationalism, a metaphysical dualism of two finite substances, mind and matter). At German and later Dutch universities he reached the highest level of education of his century. He visited Italy, France, and England. He wrote down his experiences, drew lessons from them, and incorporated them into his magnum opus in Hungarian, his autobiography, with full of testimonies, reflections, and historical sources. Much of his political work was written in Latin, and his extensive correspondence in Hungarian and Latin. However, he also spoke and wrote in German, French, Italian, Dutch, and English. He was well acquainted with the theological literature and biblical commentaries of Calvinism and also understood Greek and Hebrew texts.

The castle of Sânmiclăuș (2014). Photo via Facebook/ Csedő Attila

In 1664, he participated in the fatal hunt of Miklós Zrínyi in Csáktornya (now Čakovec, Croatia): he witnessed the fateful accident. From him we know how the wounded wild boar killed the eminent poet, the greatest Hungarian statesman of the century. This story is also included in his autobiography.

Contemporary depiction of Zrínyi’s tragic hunting accident. Photo via Wikipedia

As a Transylvanian aristocrat, he was welcome everywhere.

He knew economic matters better than anyone else in Central Europe at that time.

He was intensively engaged in problems of architecture: he himself designed the castle of Sânmiclăuș (Bethlenszentmiklós), today in the Romanian county of Alba (Fehér megye), one of the most important monuments of the late Renaissance in Transylvania. It was said that he lived in Transylvania “in the French way.”

The castle of Sânmiclăuș (August 2023). Photo via Facebook/Gauss Péter

He dedicated his life to the great task of achieving peace and security for the people of Transylvania between Germans, Turks, Kurucs, and the followers of the Habsburgs, Catholics, and Protestants. In his political reflection, entitled “Noah’s Dove with Olive Branch“ (“Olajágat viselő Noe galambja”), he defined his goal:

The achievement of perpetual and perfect peace with the Turks, the Wallachians, and the Moldavians.”

Photo via Facebook/ Drăgan-George Basarabă

During the reign of Prince Mihály Apafi I, the party dispute almost became Bethlen’s undoing. The great master of “swing politics,” Mihály Teleki, arrested Bethlen in 1676, and kept him in prison for a year. Finally, Teleki saw fit to release and employ the educated and skilled diplomat. From then on he worked with Teleki, but they watched each other with suspicion. After the bankruptcy of Teleki’s duplicitous policy, the prudent Bethlen became Chancellor of Transylvania, however the Habsburg invasion could no longer be avoided.

Drinking cup with the coats of arms of Miklós Bethlen and his wife Julia Rhédey (work of the famous Transylvanian goldsmith Sebastian Hann). Photo via Facebook/Maria Rosu

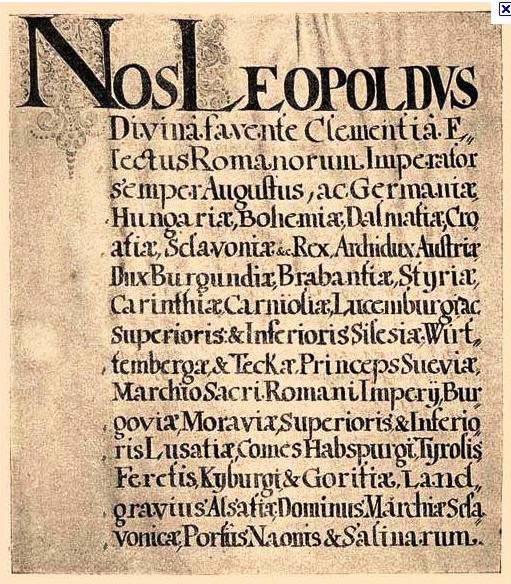

In Vienna he achieved the drafting of the “Diploma Leopoldinum” (1690), a constitutional document that granted Transylvania the greatest freedom under the circumstances, not only to the nobles but also to the commons.

First leaf of the Diploma Leopoldinum. Photo via Wikipedia

In Transylvania, the situation of the serfs became more tolerable and the citizens freer than at the same time or later in Hungary.

However, Bethlen dreamed of even more, and in 1704 – hoping for peace – he formulated his wish for the suppression of the Rákóczi movement. His goal was an independent Transylvania, under the rule of a prince from the German house.

The Viennese court saw this as a rebellion and an insult to its sovereignty. Field Marshal Rabutin had him arrested and brought to Vienna. He was imprisoned for two years until he was found innocent. As an elderly man, he wrote most of his autobiography in prison, which he completed along with his “Prayer Book” after his release. The significant and interesting book contains the summary of the worldview of a man who professed the rationalism of a Descartes, did not hate the faith of others, but was deeply rooted in his Calvinism.

He died in Vienna on October 17, 1716, at the age of seventy-four.

Via Ungarn Heute, Featured image via Wikipedia