An ill caver at a depth of more than 1,000 meters, is in such a condition that only a coordinated rescue operation can bring him to the surface.Continue reading

The experience that strikes most Hungarians in Türkiye is that wherever they mention their place of origin, they receive an exceptionally friendly and respectful reception. The immediate conclusion some draw from this that Turks understand the importance of kindness and being great hosts for their booming tourism sector. However, in this specific case, the roots go much deeper than mere good hospitality. Hungary Today has gone on a trip to Türkiye in order to investigate this phenomenon, and where best to start our investigation than visiting sites of our shared history.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

The anecdotal evidence we had about Hungarians receiving an extra-warm welcome quickly proved to be correct. From local government officials, tourism board representatives down to the restaurant waiters have made us feel special. This was also the case at our first stop, the town of Tekirdag (Rodostó), the location of one of the most important Hungarian monuments in Türkiye.

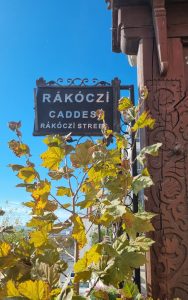

Despite cordial ties between the Turkish and Hungarian government, booming defense cooperation, or instances of humanitarian assistance, such as during the recent earthquake in Türkiye (February 2023), in Tekirdag it became apparent, that the ties between the two nations go way back in history. The spectacular entrance to the street named after one of Hungarian history’s greatest figures takes us right back to the 18th century.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

At the entrance one is confronted by Hungarian tricolor ribbons left behind from hundreds of wreaths brought by individuals or state visits paying homage to the great statesman, Prince Ferenc Rákóczi II. (1676-1735), together with his bronze bust.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Numerous reproductions of Hungarian historic figures decorate the walls of the exhibition.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

The upper floor houses the inner-sanctum of the great Prince, where he spent most of his time during his exile in Türkiye. The walls are decorated by 18th century-style floral patterns, and the curators of the exhibition made every effort to be faithful to the original look of the room.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

At the center of the room there is a ornamental chair made by the hands of the Prince himself. The seating areas are decorated with colorful Turkish textiles.

From there in 1703 Rákóczi started another war of Hungarian independence against the Habsburgs. However, most of the nobles did not support him, as they considered the whole uprising a peasant rebellion. French financial support was dwindling, and his army needed to be strengthened, while the number of men at the time was outstripped by the supply of arms and food. Ordinary, well-equipped soldiers numbered no more than 7,000, while the popular army and the commoners were ten times that number. Capable leaders, officers, horses and weapons were all in short supply.

In the winter of 1704, Rákóczi captured Nové Zámky (Érsekújvár, now Slovakia), but his success was overshadowed by the loss of the Battle of Nagyszombat. The prince personally led the army, but lacked trained officers, so he avoided major battles as much as possible, limiting himself to raiding. In his bid for the throne of the Prussian prince, Rákóczi wanted to invade Silesia, but on 3 August 1708, at the Battle of Trenčín, Rákóczi fell from his horse and fell unconscious. As the Kurutzs, as his soldiers were called, thought he was dead, the whole army scattered. They never recovered from this defeat.

On 21 February 1711 he himself left Hungary for good, heading for Poland. After Rákóczi’s departure, Sándor Károlyi, as commander-in-chief of the Kurutz armies, became convinced that in order to avoid military defeat, peace must be concluded against the prince. The negotiations ended with the Peace of Satu Mare, concluded on 29 April 1711.

Rákóczi was offered the Polish crown twice and his election was supported by the Russian Tsar, but he did not accept. On 16 November 1712, he left for England, but was not received by Queen Anne of England over the objections of the Viennese court. He then sailed for France, on 13 January 1713, he landed at Dieppe.

In 1717, he was approached by Sultan Ahmed III to organize a new uprising among Hungarians. In September, at the invitation of the Ottoman Empire, he set sail with an escort of 40 men and landed at Gallipoli on 10 October. Although Rákóczi was received solemnly in the Ottoman Empire, they did not want to hear of his wish to lead a separate Christian army. Ahmed’s chances of victory had dwindled following further defeats and the fall of Belgrade (Nándorfehérvár), so he was no longer concerned with putting the Kurutzs in the line of battle.

On 21 July 1718, the Peace of Pozharevats was concluded, in which the Porte refused to extradite the fugitives. Two years later, the Habsburg’s imperial envoy still demanded their extradition, but the Sultan, invoking the Koran, declared that he would not dare to do such a dishonorable thing. All he did was to relocate the fugitives to Tekirdag, a little further from the capital. The prince made his new home in this town by the Sea of Marmara. There a small Hungarian colony was formed around him.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

The Prince’s personal items, including his modest cross, are on display at the museum.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

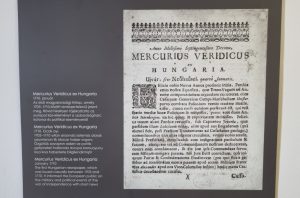

What can only be described as an 18th century version of our Hungary Today, the Mercurius Veridicus ex Hungaria was a publication intended to inform the European public of the events concerning Hungary’s Struggle for independence. It was published during the Rákóczi uprising from 1705 until 1710.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Views of the Sea of Marmara (marble) are spectacular from the window of the memorial house.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

We have found the Rákóczi house in excellent order, with further expansion of the exhibits on the horizon.

Rákóczi Ferenc House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Mikes Kelemen Books, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Where else could one find books of the 18th century Hungarian chronicler, Kelemen Mikes, than in the lobby of a Tekirdag Hotel. Rather than a commercial venture, this seems to be a sign of respect towards Hungarian pilgrims paying homage at the Rákóczi House in Tekirdag.

Hungarian Monument in a Park, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Hungarian monuments and modern statues are strewn across the city, including the ones in Freedom Park.

A tree planted by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

The sign underneath a tree planted by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán clearly show that the relations between the two nations are still very much alive and active.

Ferenc Rákóczi memorial, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Csáky House, Honorary Consulate, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

In a stones’ throw from the Rákóczi House one can visit the so called Csáky House, that also serves as the honorary consulate of Hungary. The house was named after Mihály Csáky (1676-1757), one of Rákóczi’s generals and later companions in exile.

Mr. Erdogan Erken, Honorary Consul, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Mr. Erdogan Erken, Hungary’s Honorary Consul in Tekirdag showed us around in the Csáky House, including the current exhibitions. Mr. Erken spoke fluent Hungarian.

Csáky House, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Csáky House, Honorary Consulate, Tekirdag (Rodostó). Photo: Hungary Today.

Here ends our visit to the city of Tekirdag. Our journey will continue with Türkiye’s largest and perhaps most spectacular city, Istanbul.

Featured Image: Hungary Today