The country marks the anniversary with a commemorative year full of various cultural programs.Continue reading

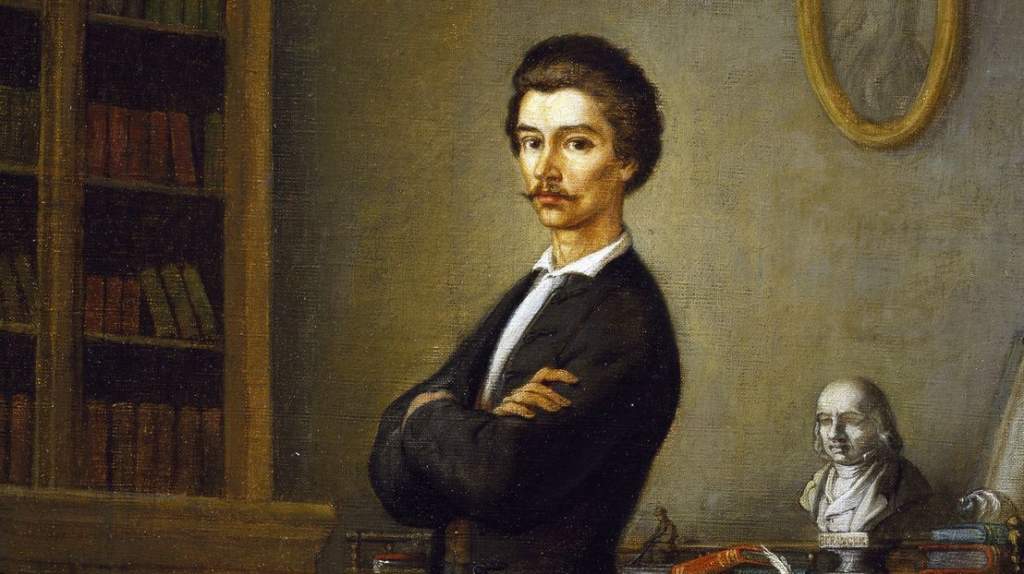

On the occasion of the Petőfi commemorative year, Magyar Nemzet spoke with literary historian László Szörényi about the Chinese reception of the Hungarian national poet.

Sándor Petőfi’s uniqueness can be perceived by people who are very distant from Hungarians and who feel a certain sympathy for them, such as the Chinese. “This is a nation who look up to us with full respect, for whom we can mention Petőfi on the same level as Shakespeare – apart from the Chinese poets, of course,” says László Szörényi.

In China there are no statues of foreign poets at all, except Petőfi, receiving four at once,

he emphasized.

Photo: Facebook/Li Zhen Árpád

He had asked a member of a Chinese delegation visiting the Hungarian Writers’ Union how many of Petőfi’s poems he thought the Chinese knew. To this, the lady replied that the last survey of educated people showed that they knew 17 of his poems by heart, which would probably be 15 more than what an average Hungarian remembers.

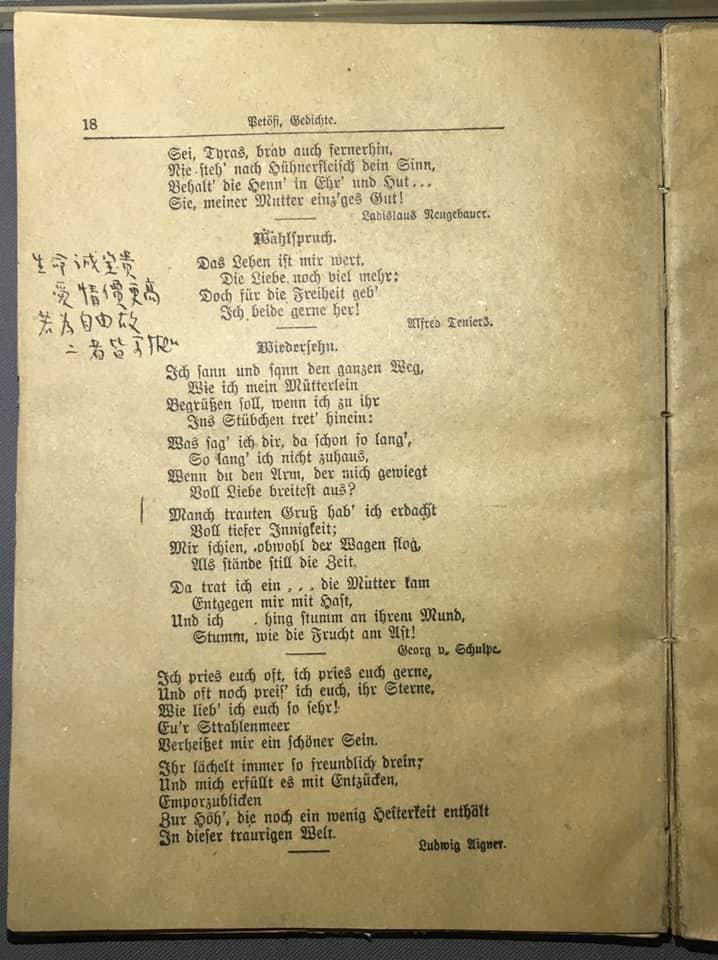

Original title: “Szerelem, szabadság” (translation: Leslie A. Kery).

This unusual Petőfi cult in China stems from the fact that the greatest Chinese writer and literary organizer of the 20th century, Lu Xun, came across Petőfi’s poems at an opportune moment. In 1908, as a young medical student in Japan, he found all of Petőfi’s poems in German in a second-hand bookstore, and after reading them, he wrote a pamphlet calling on China to catch up with world literature and have all of Sándor Petőfi’s works translated, as there was no greater poet than him. He tried to translate the Hungarian poet personally, and later he also tried to translate the works of author Kálmán Mikszáth.

‘Freedom and love my creed’ is a common saying in China, similar to Galileo Galilei’s ‘And yet it moves!’

The origin of Petőfi’s popularity lies in the striving of the Romantics for a world literature. From the Scottish poet James Macpherson, Hungarians learned that – if they want world-class literature – they must apply the standards of world literature to their own language and make the story, the choice of heroes and their background mythology so that everyone can understand it. Petőfi’s stories are created in such a way that not even fasting, walled-in Tibetan monks can resist them, says the literary historian.

When asked why a 19th-century poet can come so close to today’s readers, Szörényi again points to Chinese reception. Chinese would not love the Hungarian poet without reason: in their 5,000 years of history, everything has happened, and the opposite of it as well, so they can only accept as universal that which everyone can experience if they want to. This also applies to the art of Petőfi. The expert also cites an example from another cultural sphere: why was Homer compulsory reading in Athens before young people were called up for military service? Because those who went to the military already knew Homer’s writings by heart. They felt that Homer gave a complete picture of the world; Petőfi seems to be one like Homer, he points out.

The first Chinese translation of a Petőfi poem was published in the April 1880 issue of the Hungarian-language journal titled Összehasonlító Irodalmi Lapok (Comparative Literature Journals) in the Transylvanian city of Cluj (Kolozsvár, Románia). Wilhelm Schott, a Berlin professor who understood not only Chinese and Hungarian, but also several other languages, transcribed Petőfi’s “Reszket a bokor mert” (“The bush is shaking because”) into Chinese in Latin characters. The translated poem followed the ancient classical tradition in language and style. The translation was refined and polished by Chinese diplomat Chen Jitong, who was appointed to Berlin at that time. In 2016, a Chinese scholar, working tirelessly and persistently, succeeded in translating the text back into Chinese characters, and it was then that it became apparent that the translation was a masterpiece.

Photo: Facebook/Li Zhen Árpád

In the work titled Remembrance for the Sake of Forgetting by the great Chinese writer Lu Xun, published in the Shanghai literary criticism magazine Our Time on April 1, 1933, Chinese readers first got to know Petőfi’s Chinese version of “Freedom and Love,” which later became a famous motto. The article told the story and fate of five young revolutionaries who were secretly executed in February 1931, for their activities against the Kuomintang. Only then did Lu Xun receive the translated poem by Bai Mang, the youngest member of the “Five,” in a German Petőfi volume.

Sun Yat-sen also loved the Hungarian poet. Often called the “Father of the Nation,” he was the first provisional president of the Republic of China and the first leader of the Kuomintang. At his wedding in 1915, he cited Petőfi’s poem “You love spring” along with his fiancée, Soong Ching-ling.

Via Ungarn Heute, Featured photo via Facebook/Li Zhen Árpád