In the footseps of those who have won Hungary respect and admiration.Continue reading

In the second installment of our series looking at Hungarian monuments in Türkiye we are visiting the country’s largest and best known city, Istanbul. The close to twenty million metropolis has seen the presence and work of Hungarian personalities since the Byzantine period, a fact that local Turkish citizens seem to be more aware of than Hungarians themselves.

Bosporus, Istanbul. Photo: Hungary Today

The city spanning from Europe to Asia through the straight of Bosporus is a bustling metropolis with thousands of years of history, and listing all its noteworthy contacts with the “Magyars” would be impossible. However, we will look at the most spectacular historic monuments that some of our readers might want to learn about, or even visit in the future.

The Saint Benoit School. Photo: Hungary Today

The convent of Saint Benoit in Central Istanbul has been the resting place of one of the greatest names of Hungarian history for over a century and a half. After his death in 1735 in Tekirdag (Rodostó), the remains of Prince Ferenc Rákóczi II. have been transferred to the small church inside the medieval convent.

The Rákóczi chapel. Photo: Hungary Today

His ashes were kept here alongside his mother, Ilona Zrínyi’s mortal remains. With the permission of the Habsburg emperor, Franz Joseph, their ashes were finally repatriated to the the territory of the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1904. Today their tombs can be found in the gothic dome in Kosice (Kassa, Slovakia).

Photo: Hungary Today

The catholic church in Saint Benoit. Photo: Hungary Today

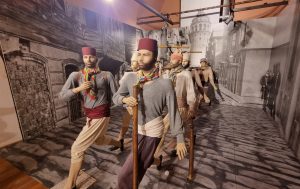

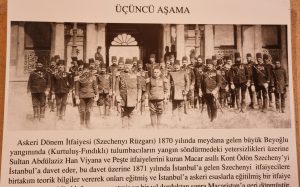

Next up on the list to see is a reminder of one of the most important contributions that a Hungarian has ever made to Istanbul. The city has been devastated by fire countless times, lives and irreplaceable historic monuments were lost to the blaze. Enter Count Ödön Széchenyi, or Széchenyi Pasa, as he is best known locally.

A portrait of Count Ödön Széchenyi. Photo: Hungary Today

The young Ödön moved to Pest at the age of 21, where he worked in almost every aspect of transport. In 1862, he traveled to London for the World’s Fair, where he came into contact with organized firefighting when he visited the London Fire Brigade. Széchenyi sought to organise fire protection in Hungary after the World Exhibition, and in 1863 the Budapest Volunteer Firemen’s Association was founded. Count Ödön Széchenyi became the first president of the Hungarian National Firemen’s Association, which was founded in the early 1870s. As early as 1869 he proposed the establishment of a professional municipal fire brigade.

Entrance to the firefighting museum. Photo: Hungary Today

When he was in Constantinople, modern day Istanbul, in June 1870, he had just arrived after a devastating fire. The embassies visited the Turkish port to organize a regular fire brigade to protect the city. As Széchenyi was there, he offered to help set up professional and voluntary fire brigades on the Hungarian model. By early 1874, the foreign embassies were already pushing very strongly for the establishment of a fire brigade, and their candidate was Széchenyi, whose name was by then known throughout Europe. The Sultan commissioned Széchenyi to set up the Turkish fire brigade under his organisation, following the Hungarian example. Under difficult circumstances and with many prejudices, difficulties and financial problems, he had to form a team and equip the fire brigade. He built a fire station and a training ground. The work took so many years that the Count ended up staying in Constantinople.

Photo: Hungary Today

Photo: Hungary Today

Photo: Hungary Today

Photo: Hungary Today

Even in his old age, Count Séchenyi went out to fires and managed the extinguishing. He was honored by successive Turkish sultans, receiving many honors and ranks, and is said to be the first Christian to receive the title of pasha without having to convert to Islam.

Photo: Hungary Today

Photo: Hungary Today

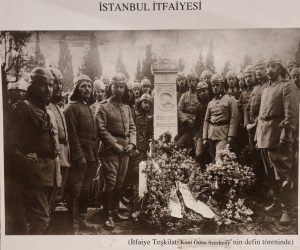

Ödön Széchenyi had passed away in 1922, and is buried in Istanbul. Every year on the anniversary of his death Istanbul firefighters gather at his grave, honoring his service to the city.

The Khedive Palace, Istanbul. Photo: Hungary Today

At the leafy suburbs of the city, overlooking the sea, one can still visit Abbas II (reigned 1892–1914) summer residence, the Khedive Palace. The Hungarian connection to the palace is the fact that it was Sultan Abbas’ unofficial and secret Hungarian second wife, Lady Djavidan, born Marianna Török von Szendrő, oversaw the palace’s development right through to the interior design. She also designed the layout of the gardens, including the planting of the trees, the rose garden and the winding paths through the woods.

Photo: Hungary Today

Next on our tour was the Liszt Institute, which serves as the Hungarian Cultural Center in Istanbul. They themselves list the most important Hungarian historic monuments on their website, https://www.turkmagyarizi.com/magyar.html. The institute offers a variety of cultural programs for its Turkish and other visitors, from organizing gastronomic experiences to art exhibitions and language courses. Because of the numerous historic ties and current positive relations between Hungary and Turkey the institute is able to operate with positive winds in its sails, but its director and staff are constantly looking at new ways in order to present Hungarian culture to a rapidly changing society.

Photo: Hungary Today

As we have reported earlier, this year we are celebrating the 200th anniversary of our national poet, Sándor Petőfi’s birth. The Institute is currently marking the anniversary with an exhibition of paintings by a Turkish artist, Haydar Özay.

Photo: Hungary Today

Photo: Hungary Today

Alongside the ubiquitous Rubik’s cube, at the entrance hall to the Liszt Institute there is also an exhibition of graphic art, depicting the exploits of a well-known folk figure János Háry from the opera composed by Zoltán Kodály. The story describes the heroic deeds of a peasant boy turned soldier who goes on to defeat the Napoleonic armies.

Photo: Hungary Today

Traces of our coexistence but also wars fought against each other are numerous, such as the scenes depicted on some of the paintings in the Harbiye Military Museum.

The conquest of Buda castle by Ottoman troops in 1541. Photo: Hungary Today

Photo: Hungary Today

“Peace to the homeland, peace to the world”, says the inscription in Hungarian behind a 19th century canon.

Photo: Hungary Today

A bust of the Austro-Hungarian emperor, Franz Joseph with a set of furniture made out of firearms that the Habsburg ruler gifted to Sultan Abdülhamid II.

Photo: Hungary Today

The battle of Mohács (1526) as imagined by painter Stanislaw Chelebowki depicts one of the most tragic moments of medieval Hungarian history, a start of a succession of foreign rules that effectively lasted until the end of World War I.

Photo: Hungary Today

The battle of Mohács must have left an indelible mark in the Turkish historic consciousness as is demonstrated by another, several meters long mural at the museum.

The Yedikule Fortress. Photo: Hungary Today

Some of those who have resisted the Ottoman rule were made guests in Istanbul’s Seven Towers Castle, also known as the Yedikule Fortress. Among its Hungarian prisoners, the most famous are Mihály Szilágyi (uncle of king Mátyás Hunyadi), Gergely Bornemissza and Pál Béldi. The last Hungarian prisoner of the Seven Towers was Count Antal Esterházy, an imperial master between 1698-1699.

One of the dungeons of the Yedikule Fortress. Photo: Hungary Today

Probably the oldest and largest monument with a Hungarian relevance in Istanbul is the former Pantokrator Monastery, today serving as the Molla Zeyrek Mosque. The imposant byzantine building hides an unexpected link to one of our greatest king’s daughter.

Photo: Hungary Today

The church was commissioned by a byzantine empress of Hungarian origin. Saint Eirene (Piroska, or also Prisca, 13 August 1088-1134), was Hungarian princess of the House of Árpád, first-born daughter of king Saint László (1046-1095), King of Hungary. She was the wife of the Byzantine Emperor Ioannis Komnenos II.

Piroska, who was orphaned in 1095 at the age of seven. At the age of 16, the country’s interests forced her to take a difficult step: in 1104 (or 1105) she was betrothed to the Byzantine Crown Prince, Komnenos II. To conclude the marriage, Piroska had to convert to Orthodoxy, in which she was given the name Eiréne (Irene). The marriage resulted in eight children. In the Byzantine court, Piroska often received pilgrims and envoys from Hungary to the Holy Land, never turned her back on her homeland, and mediated several times between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Byzantine Empire.

Photo: Hungary Today

She is known to have founded one of the most important monasteries of Byzantium (Constantinople), the Pantocrator Monastery and the 50-bed hospital that was built alongside it. The latter was the model for the construction of hospitals in medieval Europe. She died in Asia Minor while accompanying her husband on one of his campaigns.

Photo: Hungary Today

The Pantokrator monastery was built on a large plain with terraces on the hill overlooking the sea and the Golden horn. The building is estimated to have been completed by emperor Komnenos after Eirene’s death in 1124. The architect of the building is known as Nikeforos. The hospital built alongside it is estimated to have had fifty beds, and was divided into five sections, which included a library, a home for the elderly, a medical school, a pharmacy and a natural spring.

Photo: Hungary Today

History buffs on the trail of Turkish-Hungarian shared-history will certainly find enough to see in Istanbul alone, for our part, we will continue our report further to the East, near the city of Izmit.

Featured Photo: Hungary Today