350 years after their brutal fate, Hungarian pilgrims gathered in Naples to pay tribute to Protestant preachers sold into slavery.Continue reading

Since 2010, June 4 has been the Day of National Unity, commemorating the signing of the Treaty of Trianon in 1920. This treaty not only redrew the country’s map, but also severely restricted the opportunities available to Hungarian science and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA).

After World War I, Hungary suffered heavy losses not only in terms of economic and social stability, but also in terms of scientific stability. In December 1918, after the collapse of the monarchy, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences addressed a petition to the academies of the world, asking for their support in preserving the territorial integrity of Hungary. The appeal received little international response, and apart from the dissenting vote of the Czech Academy, remained virtually unnoticed.

The Treaty of Trianon had serious consequences for Hungarian science and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, not only in terms of territorial and demographic losses, but also in terms of intellectual structures, the institutional system, and sources of funding.

Exhibition “Magical Power – Knowledge. Community. Academy.” Photo: Facebook/MTA

As a result of the imposed treaty, Hungary lost two-thirds of its territory, and many centers of science and higher education remained outside the new borders.

Franz Joseph University in Cluj-Napoca (1941). Photo: Fortepan / Zoltán Aszódi

With the loss of Transylvania, the Franz Joseph University in Cluj-Napoca (Kolozsvár) was ceded to Romania, while the Elisabeth University in Bratislava (Pozsony) was transferred to Czechoslovakia.

As a replacement, the Hungarian state relocated the university of Kolozsvár to Szeged, the university of Pozsony to Pécs, and the College of Mining and Forestry in Banská Štiavnica (Selmecbánya) to Sopron.

View from the tower of the Royal Hungarian Elisabeth University of Pécs overlooking the town hall, the mosque, and the cathedral. Photo: Wikipedia

Many MTA members found themselves outside Hungary’s new borders and lost their membership because they were no longer Hungarian citizens. At the same time, the academy tried to stay in touch with Hungarian scientists abroad by establishing foreign sections. However, this proved to be more of a symbolic gesture than genuine scientific integration. The new states – Romania, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia – often put pressure on Hungarian intellectuals to assimilate or simply removed them from universities and research centers.

College of Mining and Forestry in Selmecbánya, 1906. Photo: Fortepan / Magyar Földrajzi Múzeum / Erdélyi Mór cége

As a result, thousands of professors, teachers, and students became refugees overnight. Many of them were effectively driven from their former jobs, while others left their homeland earlier in view of the deteriorating conditions.

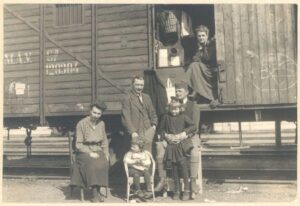

In the new university centers, however, they were often confronted with inhumane conditions: they had to live in railroad cars under miserable conditions.

After all, the decision of Trianon resulted in 400-450,000 people coming to the considerably reduced Hungary. Although exact statistics are not available, a significant proportion of the refugees were intellectuals, whose integration proved particularly difficult. The new situation led to an oversupply of intellectuals, which affected almost all scientific and cultural institutions.

Photo: Trianon 100 MTA, Facebook/ Lendület Kutatócsoport

The number of employees in public administration, higher education, museums, and archives rose significantly, while public budgets shrank dramatically. The Hungarian National Museum, for example, had only eight percent of its 1913 budget at the beginning of the 1920s.

The real value of intellectuals’ incomes had fallen to less than a fifth, and state funding for culture had also reached a low point.

In this new situation, the academy became both economically vulnerable and culturally burdened. The assets carefully accumulated before the war, mainly in the form of government bonds and guarantees, were virtually wiped out by the economic collapse. From then on, the institution’s operations depended on state support, which was provided in the form of an annual subsidy. Article I of the 1923 law sanctioned this aid, which played a crucial role in the Academy’s survival for decades.

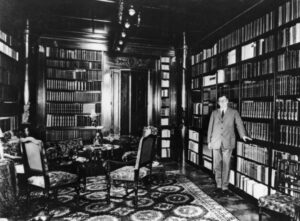

Kunó Klebelsberg in his library. Photo: Facebook/Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum

“We must not abuse the fact that the academy is in a difficult situation today in the sense that we want to exert a certain influence on the academy’s scientific activities in return for a state subsidy,” stated Minister of Culture Kuno Klebelsberg.

Trianon marked the end of an era in Hungarian academic life. The multifaceted scientific community, shaped by many ethnic groups, was replaced by a narrower, more homogeneous system that had many challenges to overcome. The scientific communities were not only geographically scattered, but also financially, organizationally, and morally weakened.

Exhibition “Magical Power – Knowledge. Community. Academy.” Photo: Facebook/ MTA

At the beginning of the 1920s, the survival of Hungarian science required not only political and financial sacrifices, but also a comprehensive reorganization. However, in the midst of the crisis, a new reconstruction process was initiated: new universities were founded and new research centers emerged. And the Hungarian Academy of Sciences redefined its role not only as a scientific institution, but also as a center for the preservation of national identity, while at the same time seeking to preserve the values of the scientific and cultural heritage of historical Hungary as a kind of intellectual refuge.

Via kultura.hu; Featured photo: Wikipedia