Local and regional leaders gathered to pay tribute to János Esterházy in Stúrovo (Slovakia). Continue reading

350 years ago, forty Hungarian Protestant preachers were sold as galley slaves in the port of Naples. The story of the galley slaves is an integral part of Hungary’s public consciousness, its Reformed and Protestant identity, and Hungarian literature—now, it is commemorated in Naples with a memorial stone. A group of Hungarian pilgrims discovered the legacy of their religious ancestors firsthand, according to a report from a Protestant news portal.

On May 8, 1675, in the port of Naples, the galley commanders inspected the condition of the newly arrived prisoners, who were ragged and broken. They had been driven here from the Carpathians to be sold as cheap labor.

Among them were forty Hungarian-speaking Protestant preachers. Months earlier, they had been sentenced to death in Bratislava (Pozsony), but this sentence was “commuted”—they were made galley slaves. There had been no war in the Mediterranean for a long time, and with no more prisoners to be had, these broken people were sold.

Freed from their shackles, they were brought aboard ships where they were bound to the rows of oars with even heavier chains.

They were branded with hot irons, and their names were entered in the “register of prisoners,” also known as the “register of death.” Galley slavery was considered by many to be a slow but certain death. It was hellish labor, requiring up to twenty hours of relentless paddling, with mouths gagged to prevent moaning. The “sin” of the preachers was simply that they had not renounced their Protestant faith.

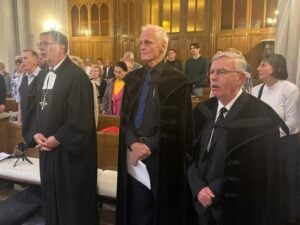

Photo: Márton Fabinyi

On May 8, 2025, in Naples, a group of Hungarian pilgrims gathered in the leafy square of the Molosiglio Gardens, right next to a pleasant harbor. Instead of the galleys and merchant ships of yesteryear, motorboats and sailboats now bob on the water. In the shade of cedars and palm trees, the pilgrims came together to pay tribute to the Protestant pastors who were sold as galley slaves 350 years ago. Those present could personally identify with the well-known story. A family from Miskolc, for example, shared how two of the deported pastors had served in their parish’s predecessor church. One member of the group had even retraced the route taken by the galley slaves (Bratislava-Trieste-Pescara-Naples) from start to finish.

The community gathered in Naples today was ecumenical: Protestant, Reformed, Roman Catholic, and Jewish believers commemorated in the park near the harbor.

Protestant Bishop Tamás Fabiny and retired Reformed pastor Péter Kardos jointly placed the pilgrimage banner in the park, which was then decorated with ribbons by the participants.

Model of a Venetian galley with prisoners inside. Photo: Wikipedia

“The galley slaves are our most important witnesses when it comes to justifying the right of Hungarian Protestantism to exist. They had two different creeds and spoke three different languages, but here, for the first time, true brotherly fellowship between Hungarian Protestant and Reformed Christians was realized,” explained Gábor Vladár, professor of Reformed theology, at the memorial service in the Protestant Church of Naples. The retired pastor said that unwavering faithfulness to the Gospel and shared suffering for Christ had always brought together the victims of Christian persecution.

Photo: Márton Fabinyi

Whether they were swallowed by the waves of the sea or they rest in Hungarian soil, we still sing their songs today as God’s wandering people, as members of the one body of Christ,”

he added.

Tamás Fabiny and Péter Kardos also gave speeches at the church event, emphasizing the profound outcome of the galley slavery: the 26 pastors who survived the ordeal did not flee to countries with legal protection but instead returned to their homeland and continued their ministry.

Photo: Márton Fabinyi

The pilgrims also erected a memorial stone in front of the church, which is to be incorporated into the promenade along the riverbank. For the time being, it can be seen in front of the Protestant church, thus becoming an official memorial to the Hungarian galley slaves in Naples.

After the Peace of Vasvár (1664), the nobility of the tripartite country—the Principality of Transylvania, Central Hungary occupied by the Ottomans, and northern Hungary ruled by the Habsburgs—sought to counter the absolutist aspirations of the Habsburg Empire. They established diplomatic relations with the dynasty’s main enemies, the French king and the Turkish sultan, in an attempt to secede. This effort is known as the Wesselényi conspiracy. In 1671, imperial troops executed the nobles who had led the uprising (Péter Zrínyi, Ferenc Nádasdy, Ferenc Frangepán) and put an end to the conspiracy. This marked the beginning of state persecution of Protestants, a period in church history referred to as the Decade of Sorrow.

The climax of the years 1671-1781 was the Pressburg trials, during which hundreds of Lutheran and Reformed pastors, teachers, and church officials were accused and sentenced without trial.

Those sentenced to death had two options to escape the sentence: either they renounced their faith and office or fled abroad. Of the hundreds of Protestant preachers and teachers summoned, 45-47 accepted the death penalty. After being tortured in prison, the stubborn pastors were driven on foot to the galleys in Naples.

The statue of Michiel de Ruyter in Vlissingen. Photo: Wikipedia

Before the sentence was carried out, the prisoners used their contacts and cultural positions to write letters and defend their rights as an organized community with strong convictions. This is one reason why their messages reached many Protestant communities abroad. In Switzerland, a fundraising campaign was organized for their release, but the money did not reach the right place. Thanks to the extensive correspondence of the German pastor and physician Nicolas Zaffius, judges and scholars became aware of the fate of the Hungarian preachers. Thanks to the intervention of Dutch admiral Michiel de Ruyter, the 26 surviving preachers were finally freed from the galleys on February 11, 1676.

Via evangelikus.hu; Featured photo: Wikipedia