During his recent lecture entitled “Choosing Sides? Southeast Asia amidst U.S.–China Rivalry” at the Danube Institute in Budapest, Professor Stephen R. Nagy has presented an entirely fresh approach to the potential and challenges hidden in Hungary’s trade and political relations to Asian nations. As political pressure and economic sanctions from the EU against Hungary are now a regretful reality, we were interested to know what role could the government’s policy of Eastern Opening play in mitigating the consequences of this state of geopolitical circumstances.

During your Danube lecture, you had a very sobering point, namely that the policy of Eastern Opening is a notable one but the Hungarian government should not forget that 80% of its trade is within Europe. Yet it is a declared policy of some of the EU’s top policy-makers that Hungary should be punished, “starved,” or “forced to its knees,” to quote only a few. We have been under de facto EU sanctions as far as European funds or Covid recovery aid is concerned. From an academic point of view, what are the best trade and diplomatic options for a country in our position?

There are some parallels here with U.S.-Canada relations. The 47th US president has recently put tariffs on Canada and called it the 51st state. Canada has 77% of its trade with the U.S. Diversifying from 77 to 67, or even down to 47% is not going to fundamentally change our economic dependency on the U.S. In a situation such as ours, one should not pick unnecessary fights. The Trudeau government has in the past 10 years consistently denigrated Donald Trump and the MAGA supporters, yet I do not think this is how a political leadership should talk. Behind closed doors, say what you want, but in public, maintain decorum.

The solution here for Canada is not to diversify (with new partners), but to upgrade its economy, its “software,” its “hardware.” At the same time, work with other partners in a smart way. The same formula should apply for Hungary. Some 80% of your trade are with the EU, you do not want to alienate them. You must instead update your infrastructure, update your energy sources. The “software” is your human capital, which needs to be updated too. Innovate more effectively at home, work with other European countries on issues like AI and other key areas. At the same time though, there is no reason to alienate Chinese or Japanese investors. You must be out there working with others, bringing back Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to Hungary. This is not a zero sum game, you must do both. To choose between European or Asian investors just does not make sense.

The reality for Hungary though is that even if Hungary reduces its dependence on the EU, it will still have to invest heavily in the European context. This must be done smartly: update human resources, invest in education, in AI training, technology training, study abroad programs for young Hungarians to help them start building those networks, business contacts, so that they can return bringing back investment to Hungary.

Prof. Stephen Nagy during his lecture at the Danube Institute in Budapest. Photo: Hungary Today

Do you think that there is an unduly tough rhetoric from the Hungarian leadership towards their European counterparts?

Well, Hungary’s policies on illegal migration are understandable, it is a country that does not have a long history of immigration from the third world, or integrating cultures. It is a Christian society, bringing in large numbers of migrants would be destabilizing. This is a red line, and other Central European countries share it. Hungarians want to prioritize this issue, which makes sense given their history. It will remain something that you will have to fight for.

On the other hand, there may be other issues that perhaps may not be on the top of Hungary’s priority list. Maybe these are not the fights that Hungary wants to pick. Find things to prioritize but also build cross-walks with the EU. There is no mutual exclusivity: you can say “no” in one area but be mutually constructive in others.

Just before the U.S. elections last year, Hungary has announced its new policy of “economic neutrality.” It is a way of protecting our trade with the East, especially with China, which is seen as problematic by some of our European partners. This policy is preempting us from being forced to choose between the Trump admin’s fairly assertive vision for future alliances, and our economic interests in Asia. Is the idea of “economic neutrality” a viable policy, or is it a myth?

Take the example of South East Asian countries, who have adopted the policy of “non-alignment.” They do not align themselves with either superpower. There is also another policy called “multiple alignment.” Those practicing multiple alignment, for instance, align themselves on trade with China, while on territorial issues, they are not. On security partnership, for instance, the Philippines are more aligned with the US, while Singapore has a quiet alignment. They trade with the U.S. and have military exercises but they do not alienate China either. Indonesia too have joint trainings with the Chinese, then they go on to have military exercises with Australia.

The multiple alignment is a model where, for instance, in energy cooperation, you look at different partners, and for trade again you pick a different set. You work with anybody who is going to help you with your national interest but you are not alienating any particular regional partner.

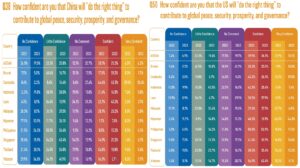

You have showed us a chart in which you have asked Asian countries which superpower they have confidence in. Interestingly, some countries who have the highest confidence in China, also have the highest number of people having confidence in the US as well. Here in Europe we are forced to align with the EU’s “either with us or against us” mentality. One side is demonized, the other stands above criticism. South Asian nations seem to be more sober and balanced in this issue. How do you explain this?

About 50 years ago, the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) was created (1967). It was established in the context of the cold war, as they did not want to choose between the Soviets and the U.S. or China. The only way they could have influence is by working together. By sticking together they had some political weight that allowed them to push back against bigger powers.

Second thing though, is that all of these societies come from a consensus-based understanding of the world. They also come from a tradition of polytheism (belief in multiple gods). Polytheistic societies are more comfortable with “grey” than they are with black and white. They are comfortable with looking at the U.S. or China as both able to have a positive influence or a negative one for that matter.

Our monotheistic society holds that there is heaven and there is hell, there is God and devil, right and wrong, etc. These are binary views of the world. There is a real strength to this idea but other parts of the world feel entirely comfortable with pooling contradictory ideas.

Chart courtesy of Stephen Nagy.

What struck me during your lecture is that you do not believe in the overwhelming importance of soft power.

No I do not. It can help with relationships, but it is not going to be the fundamental underlying force that is able to push a country to do something you want. Joseph Nye from Harvard explained soft power as non-coercive, using culture, political values, and foreign policies to enact change. This can be done through ideas or examples, for instance. The U.S. was a beacon for inspiration during the Cold War for many people, including Hungary. When I first came here, I was surprised how much people were in love with all things American. The U.S. had things that Hungary aspired to.

There are other types of soft power. I notice in Europe, also in Hungary, Japanese and Korean culture are incredibly popular. This is not necessarily soft power but rather influence, and it influences young people to learn more about these societies. It is influential because it is organic. It came from the civil societies of those two countries, and it represented something that ordinary citizens have created. This is one of the challenges that China has – it has less soft power. It is a one party system, many aspects of their society are tightly controlled. That organic and sincere portrayal of China is in many cases not what the Chinese government would like to project. People want to see wrinkles in a society, not only the flawless things, because they find it more authentic.

Soft power is interesting but we are in an era where it is not so influential. We are in an era where economic power matters, where strong leadership matters more.

There are accusations regarding China using their foreign trade and investment to project power but there is actually little evidence to suggest that they would be proselytizing in an ideological or political sense. Unlike Western powers that is, which demand conformity in values, ethics, cultural alignment: ESG, DEI, LGBTQ issues, multiculturalism, etc. Are Asian countries gaining an advantage over the West with their rejection of missionary attitudes that the West exhibits?

Modern China has been created from its experience with colonialism. They call this the century of humiliation (1839-1949). Hence they built their modern foreign policy to avoid being an imperialist power, or to impose their views, to not interfere in other countries’ foreign politics. From Deng Xiaoping onward, the Chinese approach was: do not interfere in our business, and we are not going to interfere with yours. If we look at Chinese foreign policy today, they offer untied investment or aid, there is no expectation of good governance, or to adopt their principles of politics. It is basically an agreement between two states that is non-binding.

They are not interfering and not exporting Chinese practices. But it would not be accurate to say that they are not interfering in politics overseas. There has been evidence in the Australian, Japanese, Korean case where they have done so.

One of our little Hungarian myths is that we are a bridge between East and West. I do not think that this describes reality but this seems to be our ambition at some level. How can we make ourselves more relevant in East-West relations, how can we grab a more significant proportion of the trade going on between our continents?

There are three different ways to do this. One is to identify counterparts in Asia and in Europe, and act as a mediator between these two states. You can act as an adaptor where you can connect different countries, and that needs correctly identifying where the overlap of national interest is and how different actors can work together. Hungary has that potential.

Second is to build the “hardware” and “software” domestically: building the right infrastructure so that you can transport goods better. But the software is important as well: what kind of people does Hungary need to better work with all these different groups. There is a lot of European expertise in Hungary but not so much of the one required for relations with Asia. You need to train Hungarians in Asian languages and give them regional literacy.

Lastly, how we talk diplomatically is very important. Sometimes diplomacy should not be a binary choice, because it breaks the cardinal rule in diplomacy, to keep all our options open. You are liberal or conservative, left- or right-wing, etc. These kind of binaries decrease opportunity and make it harder to have success where we are engaging. Just like the South East Asian countries: they are not choosing China or the U.S., they are choosing both.

Xi Jinping (L) with Viktor Orbán. Photo: MTI/Miniszterelnöki Sajtóiroda/Benko Vivien Cher

Last year, 40% of all Chinese FDI to Europe ended up in Hungary. I asked a Chinese diplomat what is the secret to our success, to which he replied with one word: “respect.” Is respect so central to Asian nations that it can have a direct relation to trade?

I am not sure if I would focus on the word respect, but it is more about a disciplined form of communication about China. Japan has an annual trade worth 380 billion, and they do not air their reservations about China publicly, although behind doors this could be different. They talk about forming a constructive and stable relationship with China, and the need to form complimentary relationships at the economic level.

This is a little different than respect, it is being disciplined about how you communicate. This is one of the stronger points of Hungarian diplomacy towards the region.

It is important that leaders, diplomats talk in ways that are conducive to constructive dialogue and building bridges with trade partners. China brings value to Hungary, and a slip of the tongue would not be in Hungary’s interest.

Professor Stephen Nagy. Photo: Stephen Nagy.

Lastly, I noticed that you have a Hungarian surname. Do you have Hungarian roots?

My father comes from the town of Debrecen. He was born in Hungary, he left in 1956, and ended up in Canada, where I was born. He married an Italian-Canadian, hence our household was Hungarian and Italian. I was educated in French, then I studied in English, Japanese, and Chinese at university. I have a strong Hungarian identity though. The way my father described Debrecen in my childhood is very much how I found the town the first time I visited in 1990. The nostalgia keeps bringing me back to Hungary as much as I want to chase my Hungarian heritage and learn about it. I am hoping to contribute to Hungary’s engagement with the world, in particular within my expertise in East Asia.

Stephen Nagy is Professor at the Department of Politics and International Studies at the International Christian University, Tokyo, Japan.

Featured image: Hungary Today