Last year marked a "turning point" for the Museum, with the opening of the permanent exhibition in the building that has won numerous international and national awards.Continue reading

The Museum of Ethnography is presenting previously hidden 19th century Hungarian photographs taken for the London International Exhibition. “Hungary in color. Hidden photographs from 1862,” focuses on a series of photographs of Hungarian villages of the period, unseen for more than a century and a half, since the 1862 London International Exhibition.

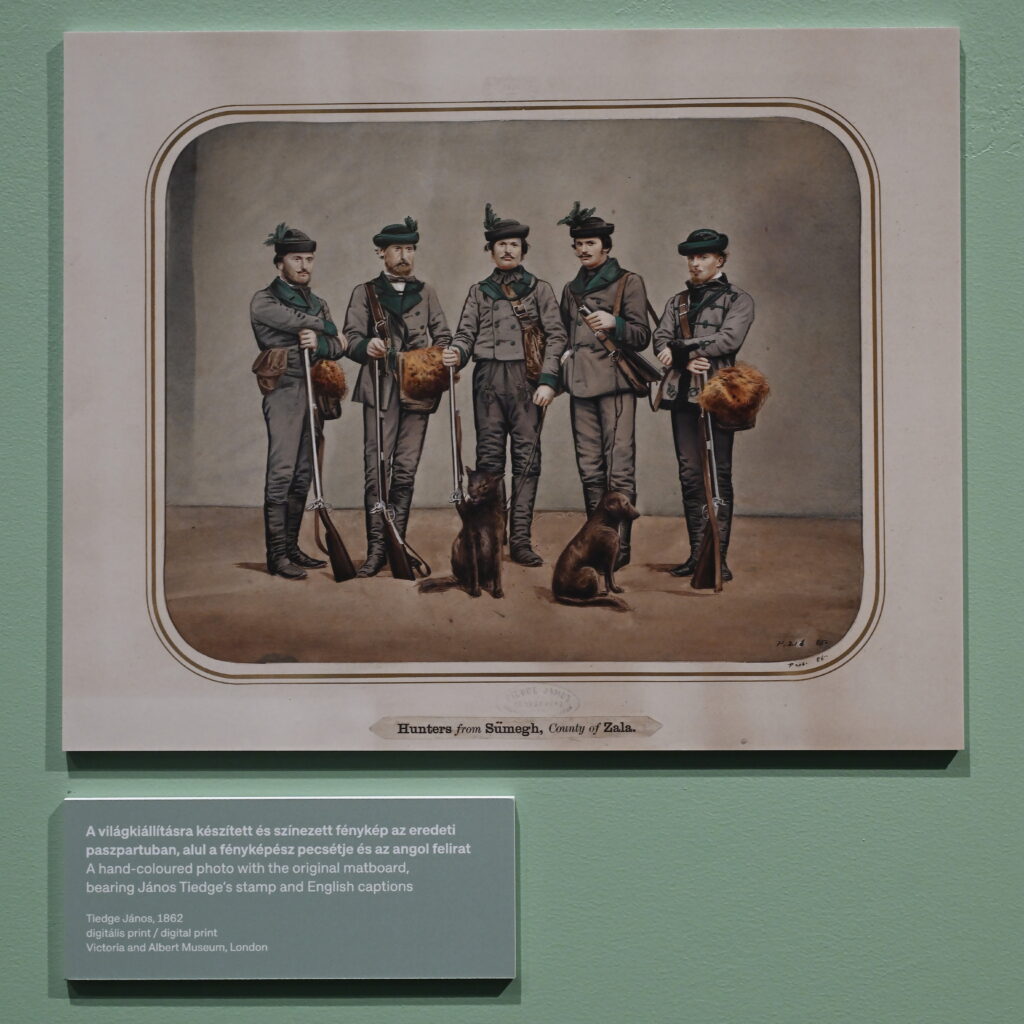

The photographs by János Tiedge, previously thought to be lost, arrived in Budapest on loan from the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, along with a series of copies kept at the Museum of Ethnography in Budapest. The two collections complement each other, recalling the former inhabitants of 36 towns and villages.

The photos, showing colorful costumes, never before exhibited in Budapest, will be on display at the Museum of Ethnography from March 5 to September 15, telling the story of their creation, from the planning to the International Exhibition.

The 1862 London International Exhibition included a Hungarian section with colored photographs of folk costumes by Tiedge. These photographs are among the earliest photographic records of Hungarian cultural history, but until now they were only known by reputation.

It has recently emerged that some of the images, thought to have been lost, have survived after all, having been discovered through digitization of the records of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

The Museum of Ethnography also has a partial set of copies of Tiedge’s images, thus the current exhibition can now include around two-thirds of the images that were once featured in London, based on the originals and contemporary copies.

A statement from the Museum of Ethnography recalls that the panorama of costume on display in London was created during a strange period of high expectations. The decade of authoritarianism that followed the 1848-49 Revolution and War of Independence was followed by a brief constitutional period from October 1860, with freedom of expression and parliamentary elections. The country was in a fever of national culture, and everyone who could wore Hungarian clothes and listened to Hungarian music.

Photo: MTI/Lakatos Péter

In the lack of tax revenues, national institutions began to flourish and strengthen thanks to the generosity of society. It was due to this that Hungary, then part of the Austrian Empire, was able to show itself at the London exhibition.

In 1861, the first call for entries exhibition attracted contributions from some ten municipalities, but that was not enough for a national panorama of photographs. Then Vince Jankó, an economic writer and event organizer, commissioned János Tiedge, a photographer from Pest, to travel the country and take five photographs of five people from each region in “decent clothes:” an old man, a middle-aged man, a young man, a young woman, and a girl.

This was not possible everywhere, hence the 76 pictures on display in London include peasants from Szeged, Pécska, and Csanád, citizens of Veszprém, an ox-cart from Pápa, workers at a machine factory, hired laborers from Káloz, herdsmen from Sümeg, noblemen from Szentgál, and hussars, all of whom offer a glimpse of 19th century Hungary.

The photographs depicted real people, not characters or ethno-national-occupational types, and the authenticity of the clothes photographed was guaranteed by the involvement of local people.

Via MTI, Featured image: MTI/Lakatos Péter