The decision might be postponed until after the presidential elections in May next year.Continue reading

After the Donald Tusk government had announced its intention to shut down the Wacław Felczak Polish-Hungarian Cooperation Institute (WFI), established in 2018, there were conspicuously few reactions even from its past supporters. Yet the decision from Poland’s left-wing government is more than symbolic – it will have an effect on those who would like to nurture the good relations between the two Central-European nations. We have asked its former director, Maciej Szymanowski about the circumstances of the WFI’s closure, and inquired about the political context in which such a decision was made.

Professor Szymanowski, please tell us about circumstances leading to your removal from your position as the director of the WFI, and what is behind the decision of Prime Minister Donald Tusk to close it?

I had the opportunity to launch two separate institutions – the first was the Czech-Polish Forum, this has been established in 2008, and it is still running. The other was the Felczak Institute, that has been set up six years ago. It is important to note that the current destruction of the WFI is a part of a wider effort. Prof. Waczlaw Felczak himself was not only active in working for good relations between Hungarians and Poles, but he was also an anti-fascist and anti-communist activist. He was a great protagonist of Central European cooperation, and in his studies he warned that if this region wants to preserve its sovereignty and live in freedom, then nations have to cooperate more closely than before. If not, Central European nations will again be passengers on a train on which they do not have a say in where it stops, neither what its final destination will be.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán pays his respects at the memorial plaque of Waclaw Felczak in Krakow in 2016. Miniszterelnöki Sajtóiroda / Szecsődi Balázs

The WFI, that I had the honor of founding and directing, was instrumental to improving Hungarian-Polish relations, especially among the younger generation. We have welcomed people at our summer camps who were committed to the Central European cooperation, so that they can meet and exchange views. The general experience was that when young people from Hungary, Czechia or Poland have met, they quickly realized that the problems they are facing in their own countries are in fact common for the entire Central European space.

Who is against the idea then that Central European nations should cooperate more closely, and why?

The Visegrad 4 cooperation has been a success, everyone who has participated in it benefited not only economically, but on a civilizational level. Our region was the fastest developing region in Europe and the world after the 1989 regime change. These countries could coordinate and could avoid working against each other’s interests. It looks like that this chapter is coming to an end.

True, but who is opposed to the idea that Central-European nations should unite and work together?

There have always been powers, either coming from the West or the East, who have offered themselves to help bring about peace and stability in our region. Instead, this has always resulted in turning neighbors against each other under the “divide and rule” principle. These powers have quickly realized that they are unable to turn us against one another if we create institutions like the Visegrad 4 was. For instance, during the 2015-16 migrant crisis we were able to coordinate our response without issues, and showed solidarity among us by voting against EU decisions that we have all rejected. But if we go down the route as today allowing others to dictate what is good for us, either from Brussels, Washington or Moscow, then this will inevitably result in serious problems. This has brought about a phenomenon that currently we are sometimes seen attacking each other on international forums. The old adage is coming true again, namely that whoever has power over Central Europe, is the ruler of the Continent as a whole.

Maciej Szymanowski with Cardinal Péter Erdő (L). Photo: Courtesy of Maciej Szymanowski

The problem is that it seems that this outside interference has its proponents inside Poland, what is more, it has serious electoral support, judging by the result of the elections. Was this a factor in the attacks against the WFI?

I think so. The Polish government, and Prime Minister Donald Tusk himself, who was once at very good terms with Viktor Orbán, now goes out to criticize the Hungarian Prime Minister at least twice a week. There is no other foreign politicians, not even Vladimir Putin or Kim Chong Un, who would be attacked so often by Tusk as Viktor Orbán. This seems to be a personal grudge. He went so far as to show support to the far-left to far-right Hungarian opposition coalition during the 2022 Hungarian parliamentary elections. Furthermore, Polish Deputy Foreign Minister, Władysław Teofil Bartoszewski, in his speech told the Sejm (Polish parliament) that it is not in Polish interests to continue with the V4 cooperation. This is a new thing, no one before has spoken so openly about not wanting to participate in this Central European bloc.

It is also a question as whether we have an independent Polish foreign policy at all. We never had such a passive foreign minister as the one today, and even if he sits down with someone for bilateral talks, there is never any treaty or agreement signed. The current Polish government has no foreign policy of its own, it completely aligns its own goals with that of the EU institutions’.

The Wacław Felczak Institute in Warsaw. Photo: Wikipedia

Many Hungarians were taken aback in recent years, even during the Mateusz Morawiecki government, by manifestations of anti-Hungarian sentiment coming from the Polish media or politicians. Not only from left-wing ones either. Obviously the two countries’ response to the war in Ukraine played a major role, but this does not fully explain what we are witnessing. How come that after centuries of friendship, a single external crisis can uproot our relationship to such an extent?

I will start with the Morawiecki years. After the Russian invasion the Hungarian standpoint was not entirely clear to Polish decision-makers. This was partly our mistake, partly that of the Hungarians’. It took long months before the first comprehensive interviews have appeared in the Polish press explaining the Hungarian position, such as the one with Balázs Orbán, the Prime Minister’s political advisor. Viktor Orbán and Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó were somewhat slow in explaining what lead to their decision. It was unclear for a long time how large the humanitarian help was that the Hungarian government was actually sending to Ukraine. They only spoke about why they are not sending weapons to Ukraine, while other countries such as Austria, were on the same plain, but they were communicating this more discreetly.

But of course there was a factor leading us back to the Polish media, a large part of which is in the hands of German owners. They were trying to exploit the differences between the two countries in order to damage Polish-Hungarian cooperation. They have succeeded in this to a large extent. But as time went on, Polish government officials have started to refer to the Hungarian position in a more favorable tune. Eventually in 2022, after meetings with Péter Szijjártó on the Economic Forum in Karpacz, they have declared that it is not the goals that they differ in, but only their approach. This was then adopted by the Polish right. Perhaps a little late, but they understood it eventually.

The Tusk government, however, only echoes the views of the expressly Hungarophobic forces in the EU. From the part of Donald Tusk this is a personal struggle against Viktor Orbán. During the pandemic it was Tusk who claimed that Fidesz must leave the EPP because they have suspended parliament and are ruling by special decrees. Fidesz have left the EPP as a result. Tusk had thus fulfilled the task that he was given. All this despite the fact that the Spanish or French governments have done the same during the COVID crisis without any negative ramifications.

All this logic had lead to the worsening of relations not only between our countries, but for the entire Central European region. Slovak and Czech relations are on an all-time low, the same applies to those between Bulgaria and Romania. The entire region has been destabilized, one early election follows another. Due to the EU’s faulty policies none of the Central European governments or parties are able to formulate a vision of a solution to the crisis in Ukraine, which puts the future of our countries in jeopardy.

The swords are out. Donald Tusk with Viktor Orbán in 2011. Photo: Facebook Viktor Orbán

Is there a way to put Polish-Hungarian relations onto a platform where our approach to Russia or Ukraine is not the single decisive criterion for deciding how we cooperate? Is there a way to bridge this issue?

Yes, but both sides have to work on this. We still have so called “friends”, who are actively working on hindering good relations between Poland and Hungary. If they succeed in interrupting this, then it will effectively end successful cooperation throughout the entire Central European space. This has been so throughout history. If the Warsaw-Budapest axis is broken, then the V4 group is paralyzed.

Thankfully there are now a few media outlets in Poland that are mediating the genuine views of the Hungarian government and are good at explaining why certain decisions were made in Budapest (DoRzeczy, Sieci, wPolsce24). They are not simply adopting the viewpoint of foreign news agencies, but are going back to the original source. In 2022 there were some Hungarian publications that for a period of time have been churning out aggressive anti-Polish articles too, but we have invited their journalists to one of our summer academies and familiarized them with some of the facts about Poland. This has changed their hostile tone.

There is an ongoing information war. Information is the most important thing in today’s geopolitics, like land was in the Middle-Ages, or energy in the 19th-20th century. Some actors, some governments exploit this fact to their goals, and this has its very concrete effects in Central Europe.

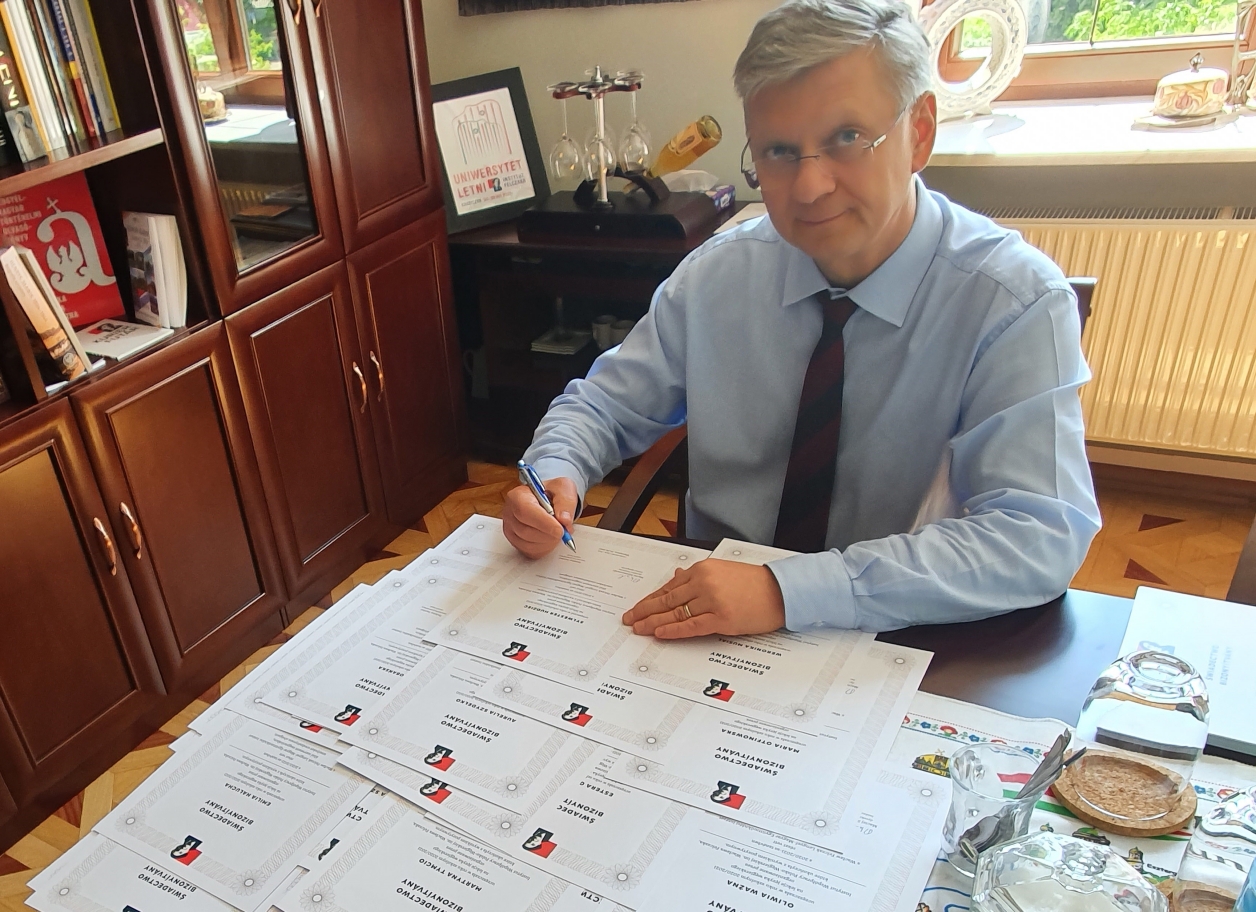

Polish-Hungarian Summer University in Krasiczyn 2023. Photo: Courtesy of Maciej Szymanowski

It is no surprise that transnational forces do have their supporters in Poland like everywhere else, but how did it come about that anti-national politicians have gained so much traction in Polish society that they were able to grab power?

First of all, the electoral law is completely different in our country than in Hungary. This has brought about a situation when the most popular party could not form a government. Alongside PiS (Law and Justice), there is another sovereigntist party, Konfederacja, which seems to be unable to put the common interest above its own party interests. On paper, sovereigntist forces have a majority in Poland. The Tusk government, that has come to power after the 2023 October elections, would probably loose if elections were held today. There has never been a government in Poland that would have lost from its popularity as fast as the current one.

Another factor is that for historical reasons Poles happen to be huge fans of unions. They have a positive experience with unions, such as the one with Lithuania that lasted for 400 years. If, therefore, an average Pole hears the word “union”, he thinks this is a good thing. Regardless of one being left- or right-wing, most people are happy with being in the EU. Some people in 2022 even hoped that there could be a Polish-Ukrainian union on the horizon, we know now that this is not going to be realized. So Poles are naturally drawn towards political unions. I must say, Czechs and Hungarians are much more sober in assessing their relationship with Brussels. This has made the former Polish conservative government’s job very difficult, when they had to criticize Brussels, as some 80% of Polish citizens are still satisfied with the EU. But if you were to break down the EU’s policies for citizens, then they would not be so keen on adopting them, or delegating their national sovereignty to a foreign power.

Still, the Tusk government had signed the migration pact. Their trick was to point to the number of Ukrainian refugees and say, “well, we have already fulfilled our quota, and you cannot send us migrants from Western Europe”. Of course Brussels will never agree to this interpretation.

It will not. Donald Tusk has claimed to be almost everything in the past, from conservative, to liberal, right- and left-wing, socialist to social democrat, etc. But he is pragmatic. In questions such as migration or EU centralization, he will remain strongly against.

Returning to the issue of the WFI, do you have any information about the Budapest branch? Is it going to continue its activities?

I have no concrete information, but the Felczak Foundation is an independent institution, it is based in Hungary. The Polish WFI was based in Warsaw, and it appears as though its over. I hope that it will return one day because we need institutions of this type.

Former President Katalin Novák addresses the V4 Academy Budapest in 2023. Photo: Courtesy of Maciej Szymanowski

Is there a hope that the WFI could relaunch in case Poland had a new, conservative government in the future?

I think so. When the government had announced its intention to close the WFI, the reaction was overwhelmingly critical, both in the right-wing and liberal media. I think this is a sign that there is demand for the re-establishment of this institution sooner than later. It should then have a better funding structure so that it could improve on its past work. If I could have a say in things regarding institutions working for Hungarian-Polish relations, I would be a huge fan of a János Esterházy institute. This should have a role in giving a platform to people who appreciate the importance of peace, cooperation, and understand that even though we are different, it is precisely this that gives us energy as nations, and is a driving force of progress. If everyone started to think the same way, that would be the end of Europe, not just of Central Europe.

It is true, that there are strong parallels between Waczlaw Felczak and János Esterházy’s thought in that both strongly believed that cooperation within the Central European space is a matter of survival and sovereignty. Its not really optional. Such an initiative is guaranteed to have a very strong Hungarian backing.

Exactly. It is no coincidence that the first Felczak Institute Prize was given to the Archbishop of Krakow, Marek Jędraszewski, who is the one handling Esterházy’s beatification process in Rome.

Featured Photo: Wikipedia