We must convince the people who want security that the EPP represents their interests, he stressed.Continue reading

On March 11, Mathias Corvinus Collegium (MCC) organized an international conference in Budapest to mark the 30th anniversary of the signing of the Maastricht Treaty, considered the cornerstone of the European Union. The main objective of the conference was to bring together experts and actors in European integration to discuss issues related to the Treaty.

In his keynote speech, Deputy State Secretary Márton Ugrósdy highlighted that the Brussels elite should first look at what the European people want and need, and this is what has been missing from European politics for the past 30 years. The discussions continued along these lines.

Márton Ugrósdy, Deputy State Secretary for the Political Director’s Office. Photo: Hungary Today

In the first half of the conference, the guests discussed whether the Maastricht Treaty (1993) could be seen as a great federalist leap or a betrayal of the European project. The guests of the event were Henri Malosse, Former President of the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC), Alvaro Silva, Deputy Director of the Royal Institute of European Studies (San Pablo CEU), Balázs Tárnok, Managing Director of the Europe Strategy Research (Institute at Ludovika University of Public Service), and Jerzy Kwaśniewski, President of the Instytut Ordo Iuris.

As for his opinion, Malosse believes that the Treaty was a good idea in principle, but that no one was prepared for it at the time, because we never had a common economic policy before. As he said,

we went too fast in the federal direction.”

Photo: Hungary Today

Polish sociologist, Jerzy Kwaśniewski, said that from a technical point of view, it was a very successful treaty, as it had been in force for 30 years and countries had been joining ever since. However, from the beginning, there have been two narratives: the community approach – a more sovereign approach – and an approach of a “federal, or even centralized political value of the EU.” According to him, these two perspectives should be considered when studying the Maastricht Treaty, because these narratives have been “fighting each other for 30 years.”

In his view,

the European community has chosen to pave its way to “a single-state European Union instead of a coalition of numerous sovereign countries cooperating on an intergovernmental level.”

He believes that Poland, which joined much later, is in fact not the beneficiary but the “late victim” of the Maastricht Treaty.

In Balázs Tárnok’s opinion, the Treaty should only be seen as an element of a so-called European integration process. “If it is an element of a process, we should consider two main factors. First, the dynamics of this European integration, and secondly, the actual influencing geopolitical factors.”

Tárnok continued by saying that public discussions about whether the treaty needs further amendments are “very much connected with the issue of the further enlargement.” Speaking from a Hungarian point of view, he said that the new states’ accession (such as the Western Balkan countries) is necessary.

If we are speaking about 30+ Member States, “it will naturally need treaty amendment, because if we do not do them, it will harm the competitiveness and effectiveness of the EU we know.”

Photo: Hungary Today

To conclude the discussion, moderator Yann Caspar asked: “Is it possible to change the way the EU functions, and is it necessary for that to reform the treaties?”. The guests all agreed that it would not be necessary to reform the treaties but a change of leadership is much needed. They argued that

we need a new EU leadership who sees the reality from another perspective.

As Kwaśniewski said, many European politicians believe that if there is no progress in European integration, the EU will collapse. That is why they want to abolish 65 cases, such as the issue of enlargement, where the power of veto still exists for the nation-states, Kwaśniewski noted. Instead of treaty amendments, it would be necessary to “stop this process of madness” instead, and “work out some new paths, new establishments of the European community,” he concluded.

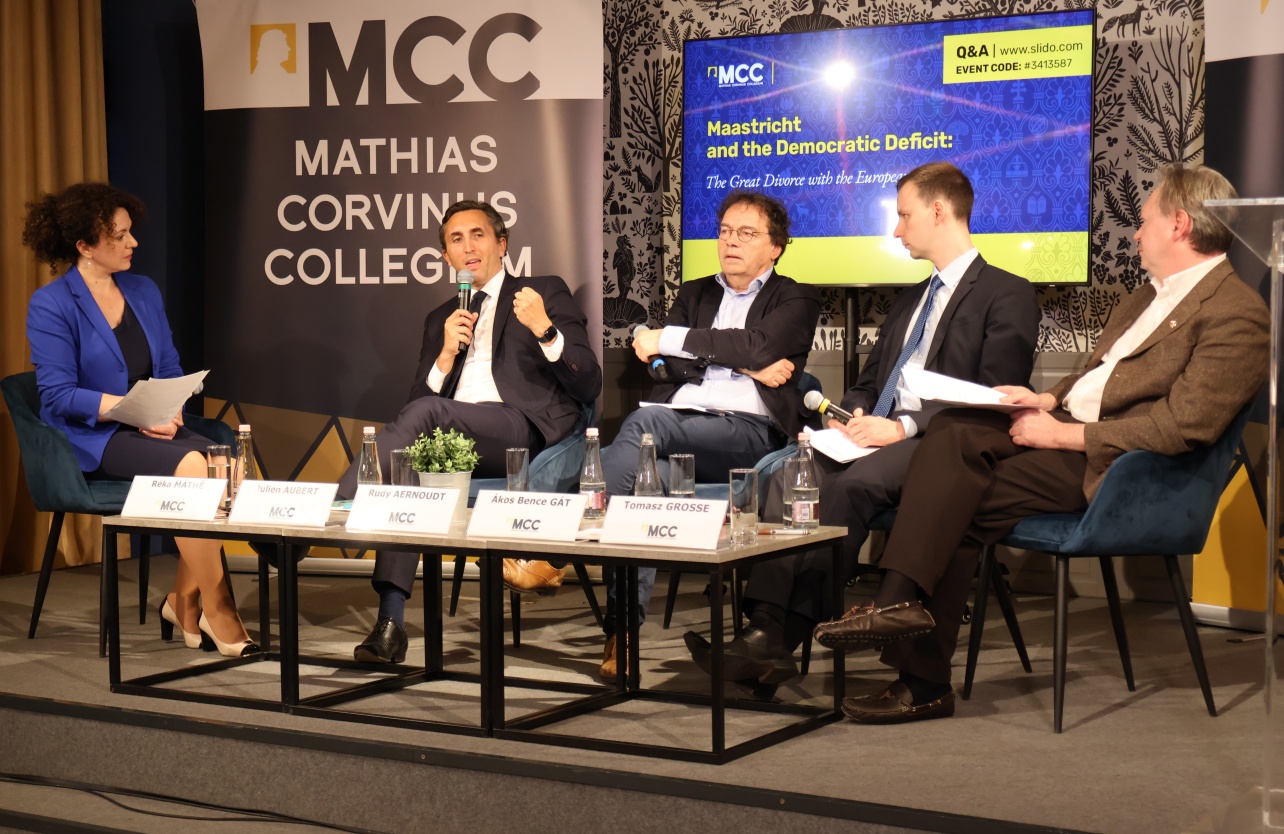

The second panel discussed the democratic deficit brought by the Maastricht Treaty. Among the guests were Rudy Aernoudt, Former Head of Cabinet of the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC), Julien Aubert, President of the Oser la France and former Member of the National Assembly, Ákos Bence Gát, researcher and Head of EU Affairs at MCC Brussels, and Tomasz Grosse, political scientist, professor at the University of Warsaw.

Réka Zsuzsánna Máthé, the moderator, drew attention to the fact that the Treaty was not accepted by every Member State the first time around, and had to be changed. In his response, Gát pointed out that currently there is not much chance of such a development, because today there is a new moral situation: “You take it or leave it,” he said, explaining that if you do not take it, you get financial sanctions. “This is the spirit of the EU today,” he summarized.

Photo: Hungary Today

The moderator noted that Jacques Delors once said that the EU started as an elitist project, and it was believed that all that was required was to convince the decision makers, not the people. In Aernoudt’s opinion, the EU should pay more attention to the real problems of Europeans.

Gát answered by saying that the cause of the democratic deficit might be that a political elite runs the EU institutions. In his opinion, the whole story of this deficit started with so-called solutions that only made things worse, and

we ended up in non-transparent lobbies, we do not know what influences decision-making now.”

The applications of the solutions are not successful, and now everything is “more like a game and not a true democratic legitimization.”

To conclude the discussion, the moderator asked the guests if it is possible to have a real democratic EU. According to Tomasz Grosse,

we need to decentralize the EU, with decisions made on the lowest possible level, and not be forced by European officials of the most powerful Member States.

Featured image: Hungary Today