Nine years after the Dictate, in 1929, Apponyi delivered a monologue in English about the Hungarian situation in front of the cameras of an American team, which has now been discovered by the news portal 444.Continue reading

102 years ago today, Hungary signed the Treaty of Trianon after the conclusion of the First World War. The Treaty proved to be a major turning point in Hungarian history, which, like the dismemberment of limbs from the body, has had a lasting societal and cultural impact on Hungarians to this day. But what if the Hungarian delegation to Paris had rejected the demands put in front of them at the Trianon Palace?

People who know their 20th century history will probably immediately reject such a hypothetical, given the Hungarian situation at the end of and in the years after the Great War. It is a fact that by January of 1920 Count Albert Apponyi and the rest of the Hungarian delegation had little to no leverage on a treaty that was composed before they had even arrived in Paris. But even in today’s Hungary, such questions around the treaty continue to come up in public discourse. In this light, this article will attempt to remain cognizant of the Hungarian situation during and before 1920 while entertaining the “what if” question, which proved to be a sliver of hope for many in Hungarian society well after the Treaty.

The Treaty of Trianon formally ended the First World War between the Kingdom of Hungary (the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy had effectively collapsed by the end of the war) and the Allied powers. It was not a question of equal negotiation. Essentially the only input the Hungarian delegation was allowed in the face of an almost predetermined deliberation was Albert Apponyi’s Trianon Defense Speech.

In his two-hour statement spanning three fluent languages, the respected Hungarian Count argued, among other things, that the Kingdom’s economy was dependent on regional specializations functioning together throughout the land. Thus, a removal of major elements would be detrimental to Central European infrastructure as a whole. He also brought up Woodrow Wilson’s 14 points, arguing that Hungarians in the separated regions should have the right to self-determination, and proposed plebiscites on secession as a solution.

Count Albert Apponyi. Photo: Fortepan / Kiss Gábor Zoltán

Despite it being said that the speech had had a positive impact on the big Entente leaders, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando, and even French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, the main damages of the Treaty were not altered. Thus, the piercing, painful fact of the matter hit home: more than two-thirds of Hungarian territory was lost, given to Czechoslovakia, the newly formed Yugoslavia, and Romania. Part of the Szepes region was given to Poland, Fiume to Italy, and Austria, one of the Central Powers, even received Burgenland. The Kingdom of Hungary’s population was reduced from 18.2 to 7.6 million, with 3.2 million ethnic Hungarians forcibly displaced. From these “torn away territories” as they are now referred to, around 400,000 Hungarians eventually moved within Hungary’s new borders.

Let’s entertain the notion that Hungary imitates Turkey after the war. The Turkish President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk said no to the Entente, ended foreign occupation, and halted a planned partition of territory. He then created a new Turkey from the collapsed Ottoman Empire and completely modernized the entire nation. For this article, his actions should be related strictly to the hypothetical context of Hungary reclaiming partitioned territories against the demands of the Trianon Treaty.

Upon attempting this relation, the glaring trump card to the Hungarian situation of the time is revealed. Unlike the army Atatürk was able to muster for his revolution, not to mention the physical distance between Greece and Turkey, Hungary’s military forces were in shambles, and there were no military experts in the chaotic Ministry of Defense at the time. Dissident Hungarian soldiers who were fed up with the war put down their weapons during the Aster Revolution, electing their pacifist leader, Count Mihály Károlyi, as Prime Minister. Worth mentioning, perhaps even for its symbolic significance, is that during this revolution, former Prime Minister, Count István Tisza was assassinated. An opponent of Tisza’s approach to the war, Károlyi followed Woodrow Wilson’s demand for pacifism and ordered the unilateral self-disarmament of the 400,000-strong Hungarian Royal Honvéd army.

Soldiers of the Royal Hungarian Honvéd in 1917. Photo: Fortepan / Veszprém Megyei Levéltár/Nemere Péter

According to military historian Tamás Révész, this was not based on the Károlyi administration’s views alone, since civil organizations and state authorities supported disarmament as well. The historian told Válasz Online that there was a strong desire for peace and anti-militarism in Hungarian society at the time. In a later interview with 24.hu, he said the Károlyi government assumed that the consistently harsher demarcation lines were only temporary, and that upon cooperating with the allies, diplomatic negotiations would solve the issue of the nation’s borders.

Károlyi’s unrecognized First Hungarian Republic was quickly replaced by Béla Kun’s Soviet Republic, but not before Romanian, Czech, and Serbian troops supported by the Allies had occupied large pieces of Hungarian territory while facing no military resistance. Thus, the stage was set for the Horthy regency that followed the communists to take on an irredentist foreign policy, a clear influence on its actions in the leadup to the Second World War.

At the 100th anniversary of the Treaty of Trianon two years ago, Pál Csaba Szabó, director of the Trianon Museum in Várpalota, said the consequences of not signing the demands at Trianon were already known. While Hungarians could have decided to physically reject the treaty, “there was no reality in refusing to sign in 1920.”

Given the hazy estimates around military strength and a state of complete diplomatic isolation at the time, Szabó argued,

the remainder of Hungary would have been on the brink of occupation, and if this had happened, the existence of the Hungarian state would have come under serious danger.”

The historian noted that the occupation of remaining Hungarian territories was already on the table for the Little Entente, giving a potential rejection of the treaty even more dire consequences in a conflict situation where Hungary had no clear military force to account for.

In an interview with 24.hu, Historian Balázs Ablonczy said that the Hungarian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference did in fact consider the consequences of not signing. They had extensively thought through all possible results and reached the conclusion that if they did not sign the document, Hungary would have faced complete economic collapse and societal upheaval.

This hypothetical situation included the potential return of the unstable Károlyi government or the proletarian dictatorship of Kun, either of whom financial expert of the delegation Sándor Popovics said would “be willing to sign for peace at any cost, even under harsher terms.” Count Pál Teleki, a member of the delegation who later became prime minister, estimated a complete collapse of Budapest’s food supply. They chose the lesser of two evils.

While the existence of the historical borders of the Kingdom of Hungary formally depended on the signing of the treaty, the fate of the Carpathian Basin was sealed well before the Hungarian delegation left for France, and arguably before the treaty was even drafted.

the history of Trianon can be validly told from the beginning of the 19th century, while its impact remains to this day.”

There is debate around when it is worth looking at the lead up to Trianon, Ablonczy said, with some historians going back all the way to the Ottoman period, while others view the development of modern nationalism in the first half of the 19th century as the catalyst.

In fact, the rejection of multiple influences on the result of 1920 in favor of the highly politicized blame game, pointing at figures such as István Tisza, Mihály Károlyi, or Béla Kun as the sole proprietors of the failure, “does not give an answer to today’s questions,” according to Ablonczy.

scapegoating will remain as long as the internal tensions within Hungarian society continue to be this strong. I find it suicidal on the long-term for us to constantly be at the throat of someone for choosing to put a flower in front of Mihály Károlyi’s statue or István Tisza’s statue.”

The issues around Trianon cannot be boiled down to one person or event, rather a series of decisions and a series of unfolding events, many of which Hungary could not influence. The situation of the time points to a lack of options, and an even worse situation with a refusal. Regarding the Treaty’s modern implications, perhaps, at the suggestion of Ablonczy, it would be more mutually beneficial for Hungarians to unite in their remembrance and strive for the improvement of cross-border relations, rather than stirring conflict over which deceased statesman bears the responsibility of a lost war.

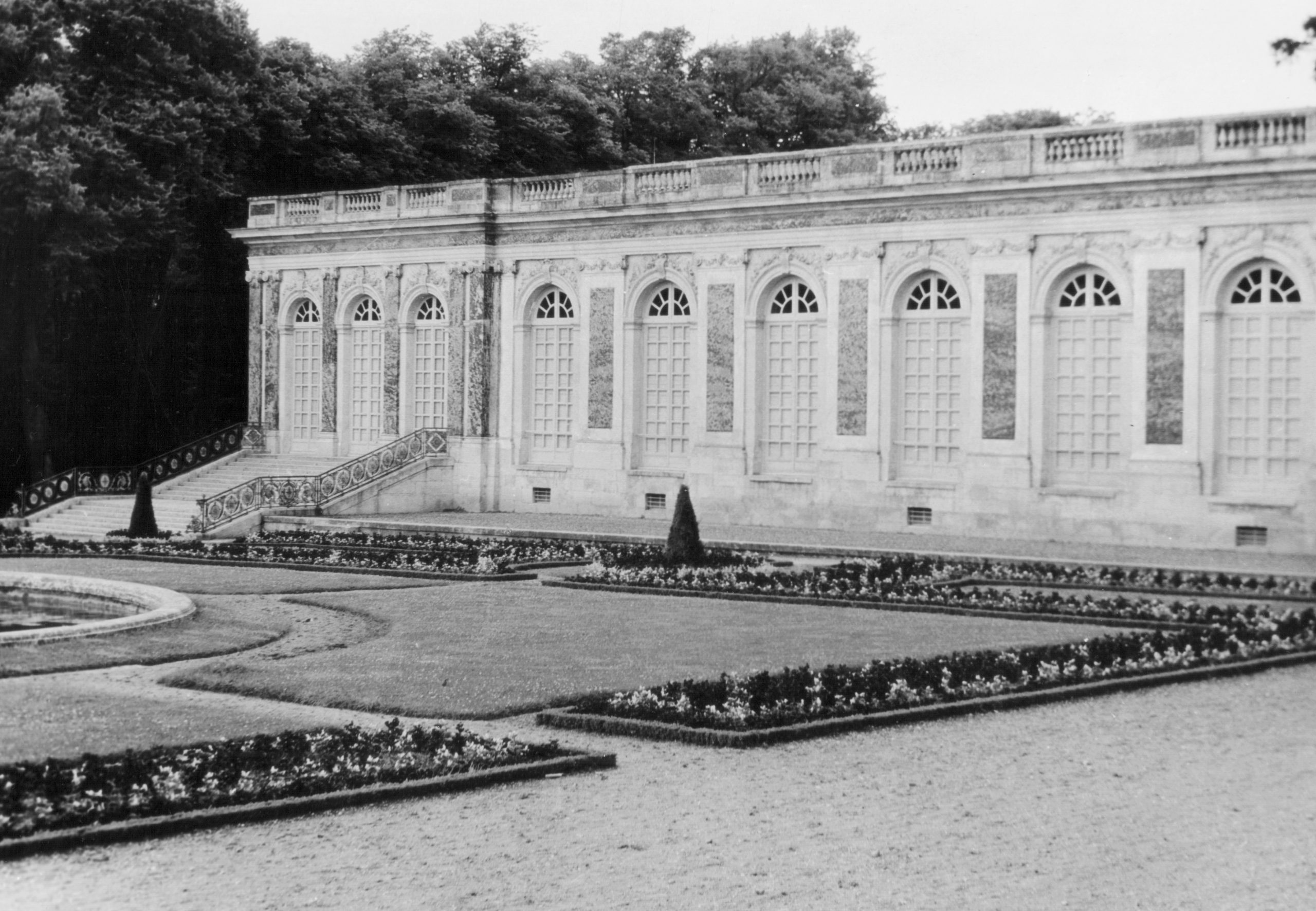

In the featured photo, the Grand Trianon Palace in Versailles. Featured photo illustration via Fortepan / MZSL/Ofner Károly