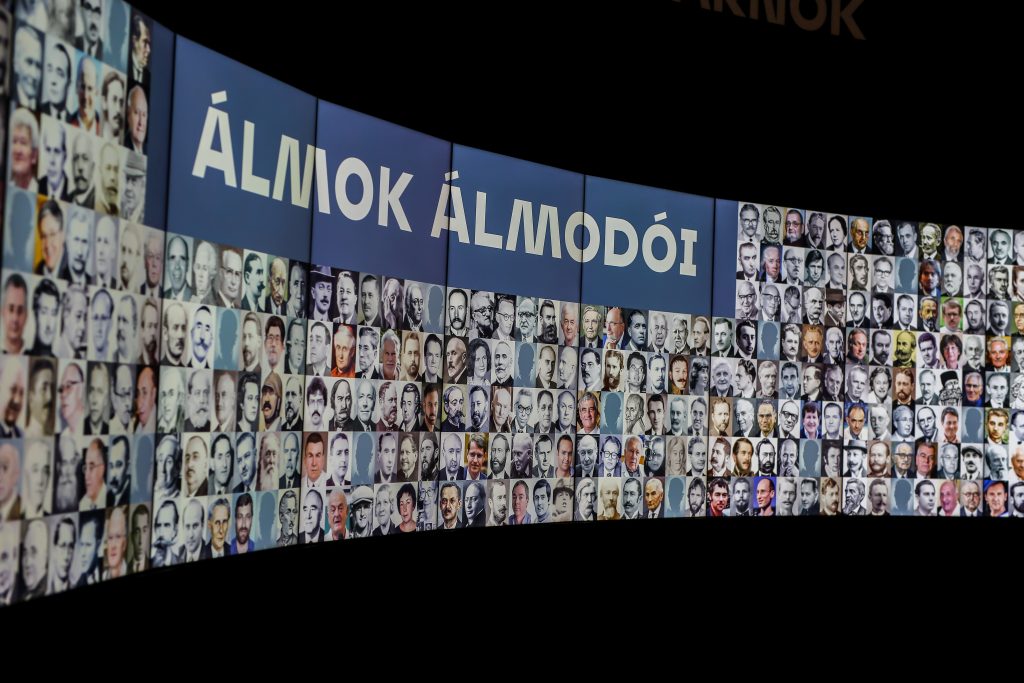

Millenáris’ new exhibition, Álmok álmodói (Dreamers of Dreams) is about everything that is science-related and which can be connected to Hungarians. It includes not only names that Hungarians are well aware of, but many others that we may not even know about, yet they invented something that shaped the world we live in today.

Rubik’s cube, vitamin C, holograms, computers, the ballpoint pen, the prevention of puerperal fever, the vaccine against coronavirus, and much more: without any of these, the world as we know it today would not be the same. What they all have in common is that we owe them all to Hungarians. These discoveries and inventions are examples of what visitors can learn more about at Millernáris now showcasing more than 600 Hungarian innovations.

Ernő Rubik, Albert Szent-Györgyi, Dénes Gábor, János Neumann, László Bíró, Ignác Semmelweis, Katalin Karikó and many more: they are the people behind these world-changing discoveries, all featured in the Dreamers of Dreams. After all, as its website says, “Science without men is but a mystery.”

The exhibition was made for the 20th anniversary of the original Dreamers of Dreams exhibition and the opening of Millenáris. However, new discoveries have been made since then; it is enough to think about the already mentioned coronavirus and Katalin Karikó.

There are so many things to look at and a seemingly endless amount of names that are mentioned in connection to discoveries. Therefore, we are highlighting some aspects of the exhibition without being exhaustive.

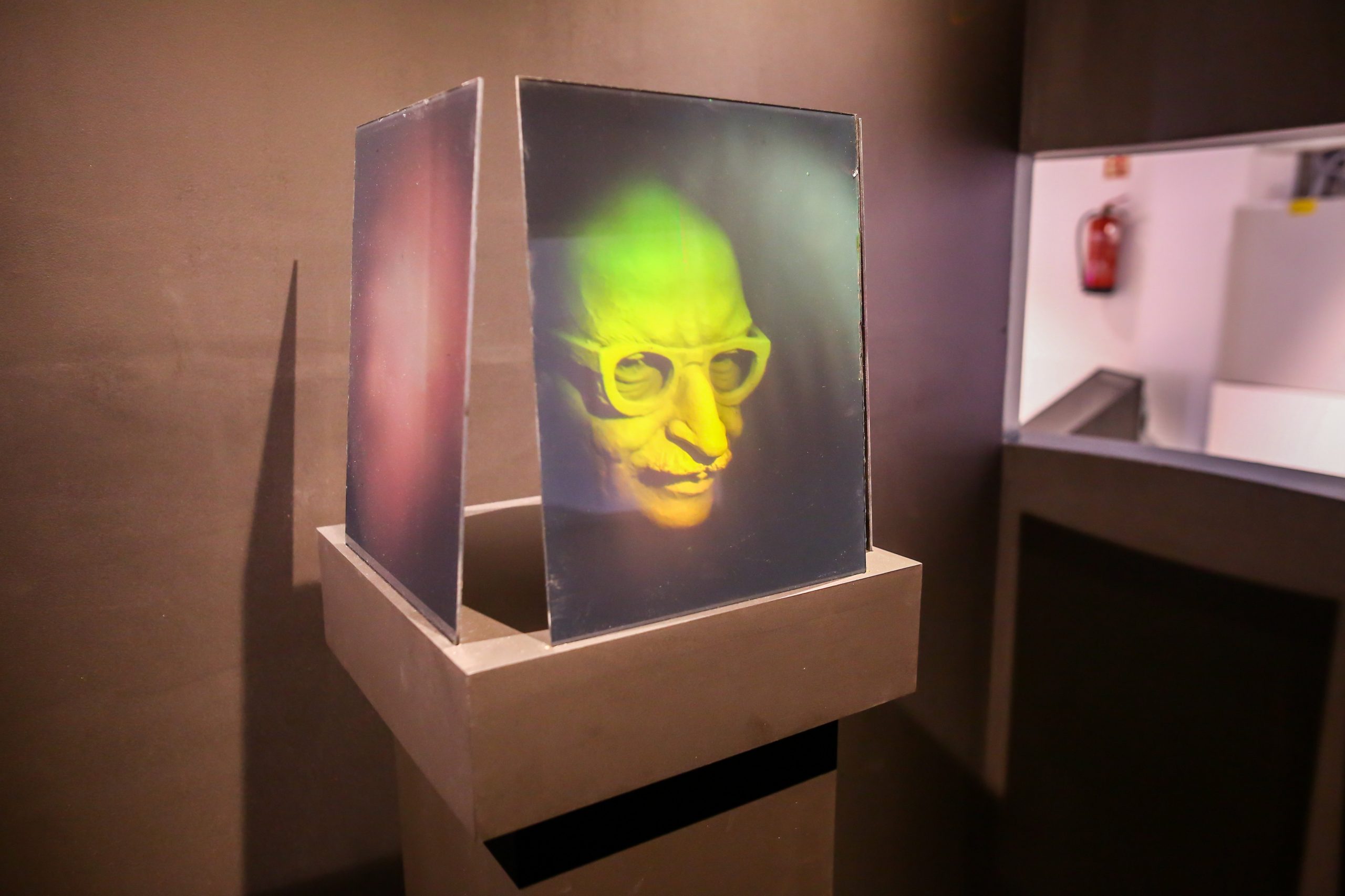

The hologram, Dénes Gábor’s invention. Photo by Attila Lambert

Let’s start with a more famous example of a Hungarian invention – the hologram – by Dénes Gábor, who won a Nobel Prize for this discovery. The exhibition clearly shows how well a hologram works: if we could not look through the plates, we could easily mistake the hologram for a statue.

Digital storage would also be different without Hungarians. For example, Marcell Jánosi invented the micro floppy disk. Today, of course, we use a different kind of storage, the evolution of which is also shown at the exhibition.

Magnetic tape, shown as an earlier form of storage at the exhibition. Photo by Attila Lambert

Some, however, still include music in their digital storage but not everyone knows that even the music industry could be different if not for Péter Károly Goldmark (or Peter Carl Goldmark) who, during his time with Columbia Records, was instrumental in developing the long-playing microgroove 331⁄3 rpm phonograph disc, the standard for incorporating multiple or lengthy recorded works on a single disc for two generations. Visitors can also see via an enlarged, interactive needle how phonograph records work.

There would be no sitting in front of our TVs to unwind after a long day at work if not for Kálmán Tihanyi, who is also often mentioned in English language technical literature as Coloman Tihanyi or Koloman Tihanyi. He was one of the early pioneers of electronic television and made significant contributions to the development of cathode ray tubes (CRTs). But there were more who contributed to the televisions in use today: in the mid-1930s, Tihamér Nemes began to study the theory and practice of television and then participated in the first Hungarian experiments. In 1938 he filed a patent application for color television.

Visitors can follow the evolution of Hungarian television in this interactive room. Photo by Attila Lambert

Here is an interesting invention that not many of us might be familiar with, displayed beautifully at the exhibition and was used in Hungarian winemaking: the “szénkénegező.” This is a device that was used to maintain the productivity of plantations infected with phylloxera for as long as possible. The soil of the vineyard was poisoned with so much carbon that the pest population had been thinned out considerably, but the vines were not yet harmed. The device looks like a big syringe and it was also used like one: injected directly into the soil next to the vine plant. Here is a picture of it in use.

The “szénkénegező.” Photo by Attila Lambert

Medicine is perhaps one of the most prominent themes of the exhibition. This is not a surprise, as it is enough to think about one of the most well-known Hungarian biochemists, Albert Szent-Györgyi, who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1937 and is credited with first isolating vitamin C and discovering the components and reactions of the citric acid cycle.

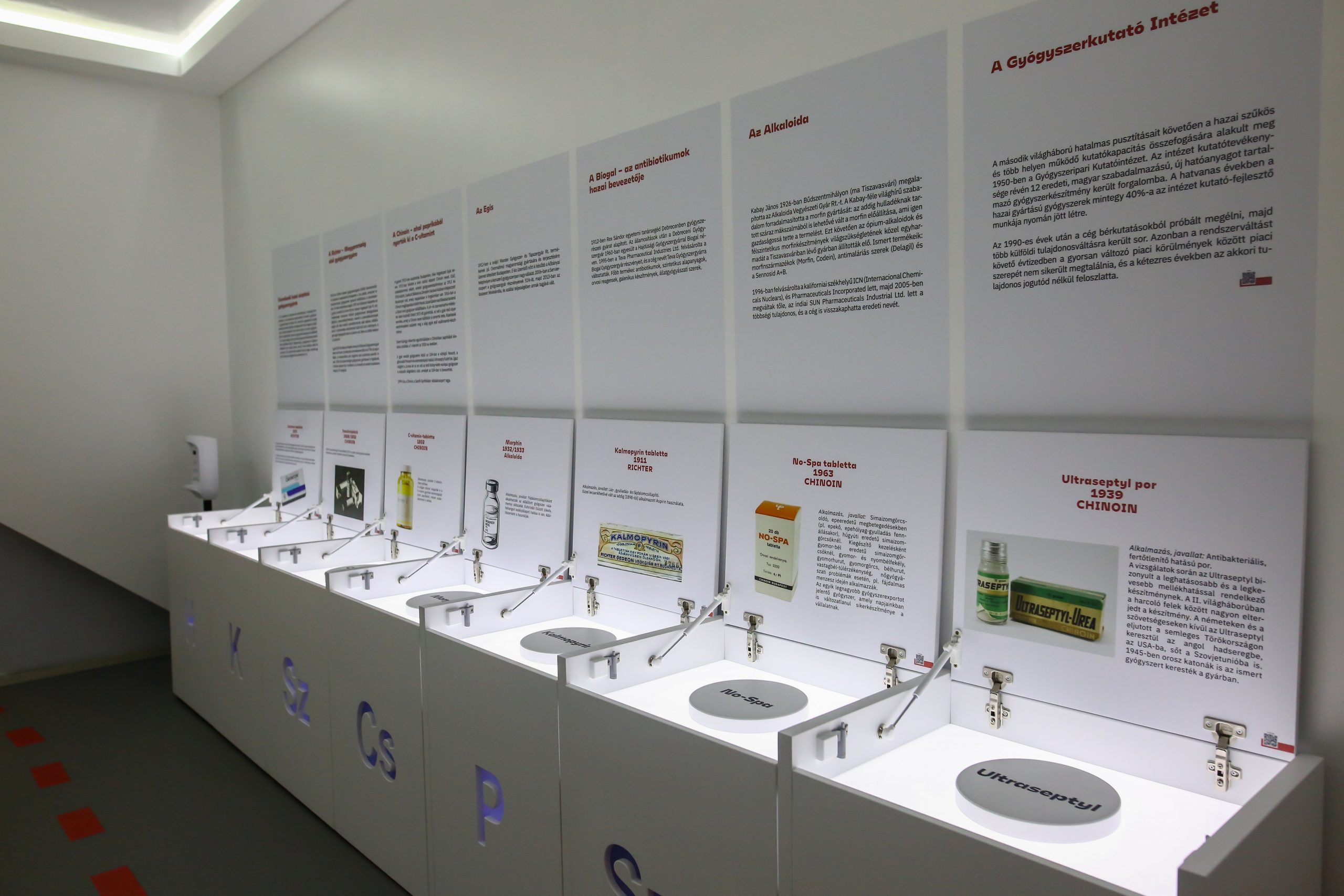

Photo by Attila Lambert

Medicines that can be linked to Hungarian scientists. Photo by Attila Lambert

A boy looking at the exhibition with Albert Szent-Györgyi’s image in the background. Photo by Attila Lambert

The view of the exhibition from the 1st floor where there are also many things to look at. Photo by Attila Lambert

The river-like display that can be seen in the picture above also has a connection to medicine: We consider the treatment strategy developed by Károly Moll, the weight-bathing cure used in spas, to be a Hungaricum. Weight bath is an underwater treatment, which aims to lengthen the vertebrae from one another, thus stretching the spinal column. The stretching process renders the restoration of the original and healthy condition of the discs possible. You can watch here how it is used today in Hévíz, where Moll lived and worked from 1920 and where he also died.

Béla Johan as a cartoon on the left, and Dezső Okolicsányi-Kuthy as a cartoon character on the right. Photo by Attila Lambert

There is a part of the exhibition where scientists as cartoon characters talk about themselves and their achievements which seems to be a good idea to draw children’s attention besides the interactiveness of the exhibition. In the picture above, Dezső Okolicsányi-Kuthy on the right, talks as a cartoon. He was a pulmonary physician who developed a surgical procedure for the treatment of tuberculosis based on the pulmonary technique. He helped to build the sanatorium in Budakeszi, of which he was the first director between 1901 and 1909.

On the left side, there is Béla Johan as a cartoon, who was one of the most important figures in preventive medicine in the 20th century. Under his direction, the foundations of the Hungarian public health organization were laid, and the centrally-run national public health service was organized. He significantly improved the epidemiological situation in Hungary by organizing the public health fight against typhoid fever and malaria, making certain vaccinations compulsory, and modernizing the drinking water supply. Furthermore, as a serologist, he is credited with the production of several important vaccines and drug stocks. (Despite his undeniable importance in medical and health policy, his unclear political role in the implementation of the Jewish laws continues to provoke public debate).

The nuclear weapon room at the exhibition. Photo by Attila Lambert.

There is no scientific exhibition about Hungarians without mentioning the Manhattan Project, which was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. Such scientists contributed to it as János Neumann (or John von Neumann), who is probably one of the most famous Hungarian scientists to this day, Leó Szilárd, Ede Teller (Edward Teller), and Jenő Wigner (Eugene Wigner).

Fact

“The Martians” is a term used to refer to a group of prominent Hungarian scientists (mostly, but not exclusively, physicists and mathematicians) who emigrated to the United States in the early half of the 20th century. Leó Szilárd, who jokingly suggested that Hungary was a front for aliens from Mars, used this term. In an answer to the question of why there is no evidence of intelligent life beyond Earth despite the high probability of it existing, Szilárd responded: “They are already here among us – they just call themselves Hungarians.” The term was also used, among others, for the Hungarian scientists of the Manhattan Project.

Photo by Attila Lambert

Many, no less important Hungarians and their discoveries could be mentioned, but as you can see above, there are so many scientists featured that we could not even fit all of them into one picture. This is why we recommend our readers to visit Millenáris themselves and bring their children along: as the motto of the exhibition goes, “The present is inside us. The future is inside you.”

Virág Dankó, Executive Director of Millenáris, said at the opening that 20 years ago, visitors were able to see that they were part of a world-class nation. This exhibition aims to give a similar experience and convey a similar message. The main aim is to show that Hungarians have not only been successful in the past, but that they still have these qualities today, she said.

Dreamers of Dreams is successful in doing so. By the time one looks at everything and arrives at the end of the exhibition, the question turns from “What did Hungarians discover?”, to “What was not discovered or invented by a Hungarian?”

Tickets can be purchased here.

Photos and featured image via Attila Lambert/Hungary Today