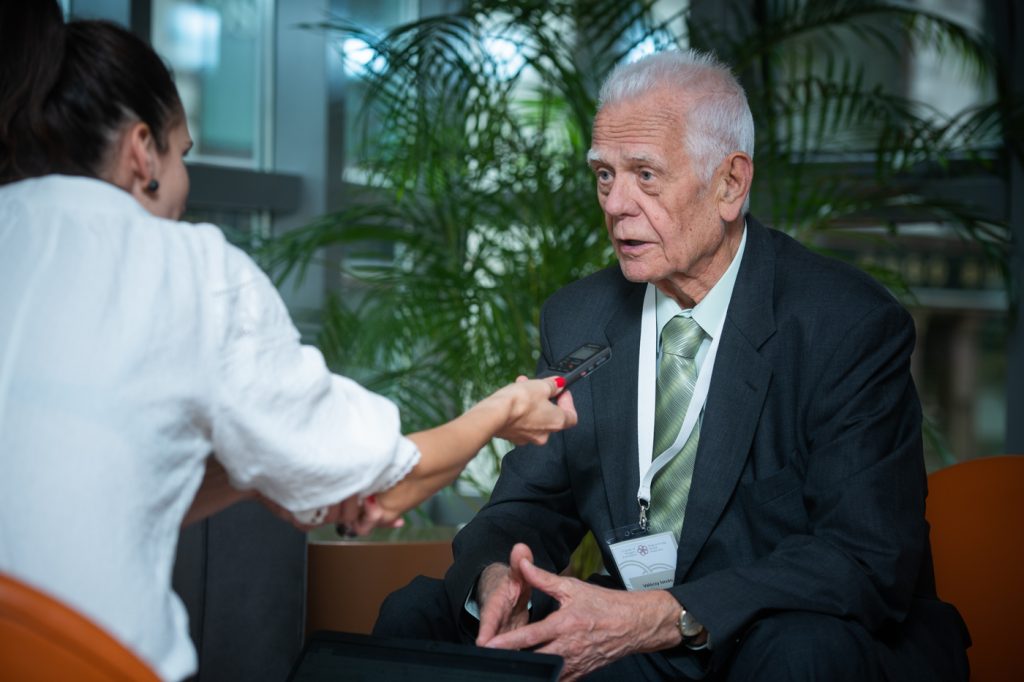

Aerospace engineer, military officer. The Deputy Head of Service for the Rákoscsaba National Guard. Sentenced to life in prison over false charges following a November 4 firefight in 1956. Working as an engineer after being freed, then as the president’s aide-de-camp following the 1989 regime change. István Válóczy tells us: when he thinks back on his unjust prison sentencing in 1956, he does not feel any hatred. We asked the Brigadier General about the revolution, the years he spent in prison, and the Kádár regime’s retaliatory policies. INTERVIEW.

Already at the age of 8 you wanted to be an aerospace engineer. Later, you acquired a diploma for this, and you were even promoted in 1956. Then the revolution came. Did this ruin your career before it even began?

Not entirely. I finished school at the University of Technology’s Faculty of Military Engineering. I decided in December of that same year that I would not sign the officer’s oath, essentially decommissioning myself. After decommissioning I worked at a telecommunications factory, performing the job of a mechanical engineer for a year. This is when I was called in to be interrogated on the issue of a certain firefight which occurred in Rákoscsaba on November 4, 1956. In other words, I could continue my profession under normal civilian circumstances all the way until 1957. Then, during Christmas of 1957, on December 24, which was one year after the revolution, I was taken in for interrogation. I would not be able to celebrate Christmas at home with my family, despite my mom cooking my favorite dish, rabbit hunter’s style, which I did not even get the chance to eat. (laughing) And the verdict was declared in June of 1958.

Exactly what happened on that Christmas day? Did the ÁVO just show up at your door?

No, I instead received an invitation for a hearing of witnesses. 10 people were brought before the jury over a 1956 firefight. Ultimately, they made me a first-degree defendant, and since I was a military officer at the time, the matter was put in front of a military court. After the first day of hearings, all they told me was that I should return to answer 1-2 more questions. This did in fact happen, then, following the recording of proceedings and hearings, two men came to me, looked at me, measured me up, then informed me that I was under arrest on the grounds of my own testimony. Later the investigator even said that “sure, you said all these things, but how much could you have done?” this was the foundational position of the court.

What are all these things that you did? And what exactly happened in Rákoscsaba on November 4, 1956?

The Soviets came into Budapest at the edge of Rákoscsaba, they did not even come further into the district, except for two of their vehicles, which likely got lost. On the main road, at the military accessory building, these were fired upon. The tire of one of the vehicles was shot, making it immobile. The soldiers jumped out of one of them, and this is when the actual firefight began. Luckily there were no civilian casualties, but based on the report of the Soviet command, it was later announced that one officer and two soldiers died either on-sight or later. Those living in the neighborhood did not see corpses. I was not there at the time; I was eating lunch at home when the event unfolded. I heard the gunshots, the explosions, but I did not go there. What is certain is that the whole thing happened out of the blue, it was not organized, despite what had been claimed in the lawsuit, an accusation by which I was ultimately convicted.

What exactly was written in your indictment? Why were you sentenced to life in prison?

At the first level I was only sentenced to 15 years. Two of the 10 defendants had been present with weapons. They were sentenced to death by hanging. At the second level, convicts were sentenced to life in prison, and my sentenced was lifted to this level. Since there were three deaths, three severe sentences had to be given out… In the K.U.K. (The Austro-Hungarian Army – Editor) this was called decimation.

Can you remember what your first thoughts and feelings were when you heard this second level verdict?

At the first level, 15 years did not sound so dangerous, but I will tell you honestly that I could not take it seriously, since I knew what I had done, more specifically what I had not done. They were accusing me of organizing this firefight. A firefight which was sparked spontaneously and for which they could not say who fired the first shot. Clearly it was whoever shot the vehicle, but how that person ended up there is not known for certain to this day.

Did you use a weapon at all?

In the ledger it had been written that we needed to face the Soviets with weapons, since we were ordered to do so. Once again, I emphasize that this is not true, the whole firefight developed spontaneously. Our assignment was the protection of objectives, which they washed together with their accusation. Furthermore, they alleged that I had given the order. With retrospect to the situation, there needed to be a leader for these 10 people, and it appears I was especially suitable for this due to my university background, my military past, and my father’s professional past. These were all hefty circumstances that could be used against me. I found out in a later study of the documents that two of the other defendants, who would later be convicted as well, had mentioned my name during their hearings. All they said, however, was that I was there. But no, I did not use a weapon.

Related article

Faces of the 1956 Revolution - with Archived Photos!

There are a couple of 1956 freedom fighters and groups of fighters who became well-known, either by their acts, their martyr deaths, or by archived photographs appearing in international newspapers or domestic publications. Some were even painted on firewalls of the capital. The Széna square group of freedom fighters and the Pest lads are all […]Continue reading

Did you know anyone among the accused?

Yes, of course. After all, most had been working at the National Guard, they took care of policing activities, they guarded entirely specific objectives and oversaw policing patrol services. I was a kid from Csaba (Békéscsaba, southern Hungary – Editor), and part of them, part of us, ended up in the Guard through boy scouts. There were 10 people there out of roughly 100.

The interrogation techniques of that regime were inhumane and merciless, this was especially true towards the 56ers. How did you live through this experience, knowing that they may hurt you?

At the age of 24 I was a bit naïve, but I saw through things very quickly.

When I was arrested at Christmas, I was taken to the investigator. They knew that I had a 1.5-year-old son, who I needed to leave right at Christmas… so they took me to the investigator, who purposefully spoke in front of me about how much his son loved the Christmas gifts he had received.

This was a so-called “soul massage,” where the officer spoke about this on the phone in front of me intentionally. I saw through this and did not let it break me.

Your son was 1.5 years old during that Christmas. When he grew up, did you talk to him about how he experienced this event, and how he was impacted from being without you for six years?

He remembers that I was not home for a very long time. He was born in 1955, and the verdict was declared in the summer of 1958, but he remembers many things. The child could not be brought in to speak to me, but my first wife spoke to him a lot about me while I was incarcerated. He had memories and waited for my return. The closest thing we had to interaction was when we were paid and could purchase books from book shops that were set up every now and then, where I could buy him a book and mail it home. This was perhaps the only interaction between the two of us, other than that I only received pictures of him.

How did it feel when you stepped out of prison and were finally able to see him again?

I was freed during the period of great amnesty in 1963, the last hour of its last day. It was a difficult 10 days, waiting to see whether they would free me, and if so when… I knew that my father worked at the metropolitan tram railway, and I knew where to find him. He sent word home that I was out and called for my son to come see me. When we met, we embraced one another. (emotional)

Paradoxically, you were able to “use” your years in prison for positive things. If I understand correctly, there were opportunities to improve your skillset, for example, learning languages and working. What was the bonus that you achieved in knowledge or spiritual development while in prison?

At first it was emotionally straining, since they had sat me down unjustly, based on a masterfully crafted artificial situation. Additionally, they had me sign one of the ledgers without even having read it.

It was difficult, but I have to say that taking prison seriously was not allowed, as strangely as that sounds. If a person ends up in a difficult situation, one which they had not seen themselves in before, and for my part prison was such a place, all their “lacquer” falls off them. If there is no person underneath that “lacquer,” then that individual has nothing left for them. If THE person is still there after this shedding, then only that person can decide whether they want to get out of that situation properly or not.

Looking at the lawsuits of that time (for example Rajk’s lawsuit) I was counting on being freed in a few years despite being given life in prison. In 1959 there was an interstitial period of amnesty, but at that time only people who had fulfilled some role in the party were set free.

A day in prison was long, I needed to consciously pay attention to making sure it was spent meaningfully. After having flown since the age of 16, I was used to being placed in unexpected situations. In these situations, one needs to react quickly, since there is no time to pull out a book and check what the protocol is. I needed to summon this way of thinking once again. It was so difficult that later I turned to transcendental meditation, which helped a lot.

Related article

Why did Beethoven's Egmont Overture Become the “Hymn of the Revolution”?

The powerful melody of Beethoven intertwined with the events of the revolution, from the night at the Parliament, to the siege of the radio building and to the point when Imre Nagy announced at noon on October 24 that those who would immediately lay down their weapons would receive amnesty.Continue reading

Perhaps the most difficult thought was that I could not go outside, the door was closed in front of me, and I could not do anything about it. What were our opportunities you ask? During the day we worked, in the afternoon we were in our cells. When I worked in the translation office, we could ask for language books, and I could improve my knowledge of foreign languages. Before I could work, I was locked in a 2×4 meter room with two other people. One was a young Orientalist, who was convicted of treason, the other was a Romani boy. After the war a group of Roma in Szabolcs ate a teacher, he was somehow in this gang as a minor. This Romani boy knew the castes of the Roma, all the way to their Indian roots, speaking of them often. The Orientalist found this especially interesting. I listened to them when they spoke to each other, and I learned a lot from these discussions.

I imagine it was not easy to be content after being freed, since 56ers were not welcomed with open arms out there. To what extent did the ÁVH go in trying to reach after you or your family?

Life was not easy after I was freed either, I could not settle just anywhere. I was lucky, however, since many of my previous group members were working at the Ikarusz bus factory. In fact, there were buses that had bodywork planned by aerospace engineers. This is how I ended up in Százhalombatta, where I was hired as an investment engineer. I had good colleagues at both places. Of course, I needed to always look “behind,” paying attention right and left. I had to work in a way that would make it impossible for them to intrude.

There was a wage category with which I was hired. I had to catch on to the fact that my work was not the determiner of whether I got a raise or not. For a long time even in the bearing factory my pay was below 2,000 forint. I ended up there in 1968 and could not leave for 12 years, they would not let me go.

There is another very exciting event in your life, systems theory. Countless books and publications are available under your name, and you have lectured on the subject as well. Did this career path develop in this way since work in aerospace engineering and flying was made impossible after the events of 1956?

I began involving myself in systems theory in prison. When I was sent from the translation office of Vác to the collecting office of Kőbánya, I was the head of an editorial team. We worked out of technical journals. At the time web planning was known in America, they had been using it since the start of the 50s. For us, it began taking hold at the beginning of the 60s. I was able to join a web planning lecture in Százhalombatta after I was freed. I used this knowledge in the fields of investment and maintenance. At the time we did not call these things systems of organization, but we later found out that this was what we were working with.

As investment inspector, it was my job to make agreements with contractors. It was my job, among others, to tie the beginnings of contracts with their following parts. An individual working this job does not necessarily need to have an understanding of the profession, but rather an understanding of the system, and how that system operates.

Let us take a jump in time once again, all the way to the regime change. After 1990 you became the aide-de-camp of then-President Árpád Göncz. What sort of tasks did this entail?

During the regime change it was partially thanks to my connections that I ended up next to the president. I worked together with Árpád Göncz in the translation office in prison. There were many of us, around 40 people. He looked for two of us after the regime change, the other person being a former Ludovika officer, Laci Zólyomi, a colonel of the general staff who was also imprisoned after 56. He knew that I was also a soldier and that I worked in aerospace. He sought us out because the aide-de-camp post is one of trust. Who were the people within the military office who could oversee the function he represents, and make it a reality in practice? The military office developed with five people. This joint work lasted throughout Árpád Göncz’s first term. This was the function of a public official, in accordance with the constitution (the one from 1990) since the president was the commander in chief of military power as well. It must be fulfilled all the same in peace time, and we helped in this professional, non-political task.

On October 23, how do you typically look back and remember the events of 1956?

I involve myself in societal responsibilities to this day. Through the active initiative of Béla Király, a “56-er National Guard Council of Tradition” was created for the 60th anniversary. At his request I took over the post in 2008. Unfortunately, we have not been able to get together due to the pandemic. Prior to it we organized annual conferences in which we recorded the history of the National Guard. We published a book on this as well. We continue to work on this history with remaining members and have sought out those who were once in the National Guard. Furthermore, we even remade the 56er badge for them. Of course, we have records, however I cannot tell you how many of us are still alive. I am certain, however, that back in the day there were hundreds of us. Other than this, we also have a Hungarian national aviation foundation, which we created more than 30 years ago. The “Goldtimer Foundation” protects the memories of Hungary’s aviation history, since prior to its creation, these things were not protected, recorded, or organized by anyone.

Is there some sort of dominant emotion which defines this date for you?

I feel sorry for those who took part in the regime’s construction. It was not easy, for example, to take on the work environment of being an informant, and of course I know that it was not easy to say no to the job, but also that it was not mandatory.

There is no hatred in me. What would I gain if someone else would be punished as retribution for the 30 years that were taken from me? What I know is that the judge who condemned me later went insane. Somehow, in some way, justice always ends up falling back in place.

Related article

The “Bear” who dodged bullets, but luck found him – the life of 1956 emigrant and patriot József Komlóssy

József Komlóssy dedicated himself to serving the global Hungarian cause after his trip through Transylvania in the early 60s. Above all else, he strove to support the rights and interests of those Hungarian minorities within the Carpathian Basin.Continue reading

Photos by Tamás Lénárd/Hungary Today